Hiram Young - Appreciating His "Useful Life"

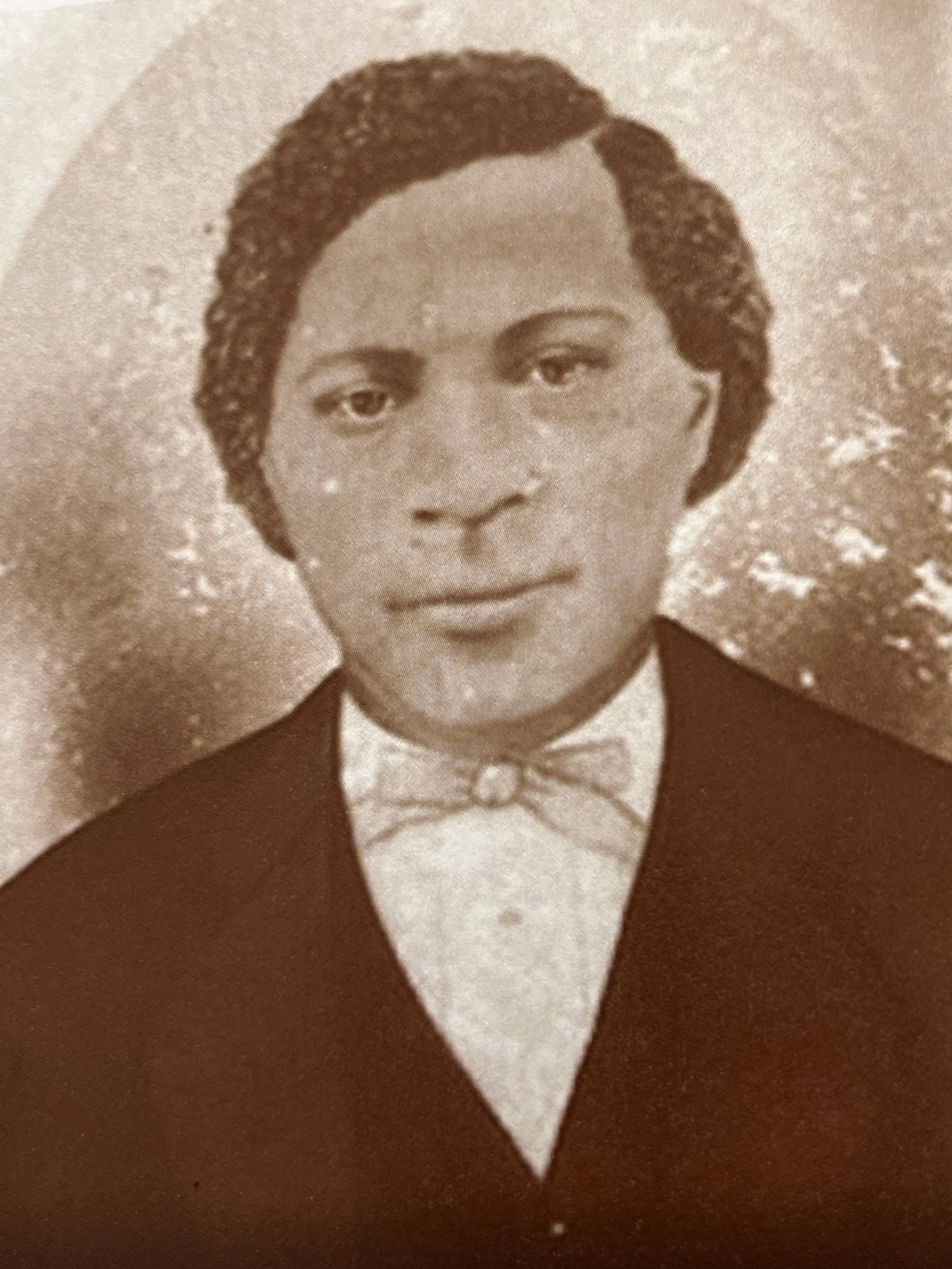

Hiram Young, the former enslaved person who later became a prosperous Independence wagonmaker, today represents to his contemporary admirers a legacy of self-empowerment and personal triumph over injustice. JCHS Image No. PHL 5339.

This month the Jackson County Historical Society observes Black History Month in two ways.

First, the February JCHS “E-Journal” examines how the legacy of 19th century African-American wagonmaker Hiram Young continues to be curated and maintained by scholars and admirers.

One example is the work being done by representatives of Truman Heritage Habitat for Humanity, which operates out of the former Hiram Young School in Independence. To learn more about the mission of Truman Heritage Habitat for Humanity and to support its efforts to develop a “Historical Museum Classroom Space” at its headquarters at 501 N. Dodgion St., go to trumanhabitat.salsalabs.org/museum/index.html

Secondly, the Society has installed a Black History Month exhibit at the Mid-Continent Public Library’s North Independence Branch at 317 West U.S. 24. This display includes information on notable African American individuals in our county and the impact they made in our community.

BY BRIAN BURNES

At first glance, the artifacts on display in the former Hiram Young School in Independence are not remarkable.

There’s a clock, a green chalkboard, and an assortment of antique school desks.

The school was named for the prosperous African American wagonmaker who outfitted the freight haulers and emigrants leaving Independence in the 1850s to follow the Santa Fe, California, and Oregon trails.

Those who have custody of the building today, however, consider the everyday items to be community heirlooms that deserve to be curated and displayed to illuminate the historical figure of Hiram Young as well as his continuing legacy.

Christina Leakey, president and CEO of Truman Heritage Habitat for Humanity, which occupies the former Hiram Young School, would like to see preserved school artifacts professionally displayed and interpreted in a museum classroom. Photo courtesy of the Jackson County Historical Society.

“There is an ongoing fundraising campaign to support completion of a museum room that will properly interpret the history of the Young School and its association with Hiram Young,” said Christina Leakey, president and CEO of Truman Heritage Habitat for Humanity, which has occupied the former school since 2022.

An enslaved person who purchased his own freedom, Young later acquired other enslaved individuals and then hired them at his wagon works, allowing them to eventually buy their own freedom.

Young’s accomplishments, achieved many years before Missouri legislators banned slavery following the Civil War, long has been recognized in Jackson County. The Independence city seal, adopted upon the community’s 1849 incorporation, features a covered wagon.

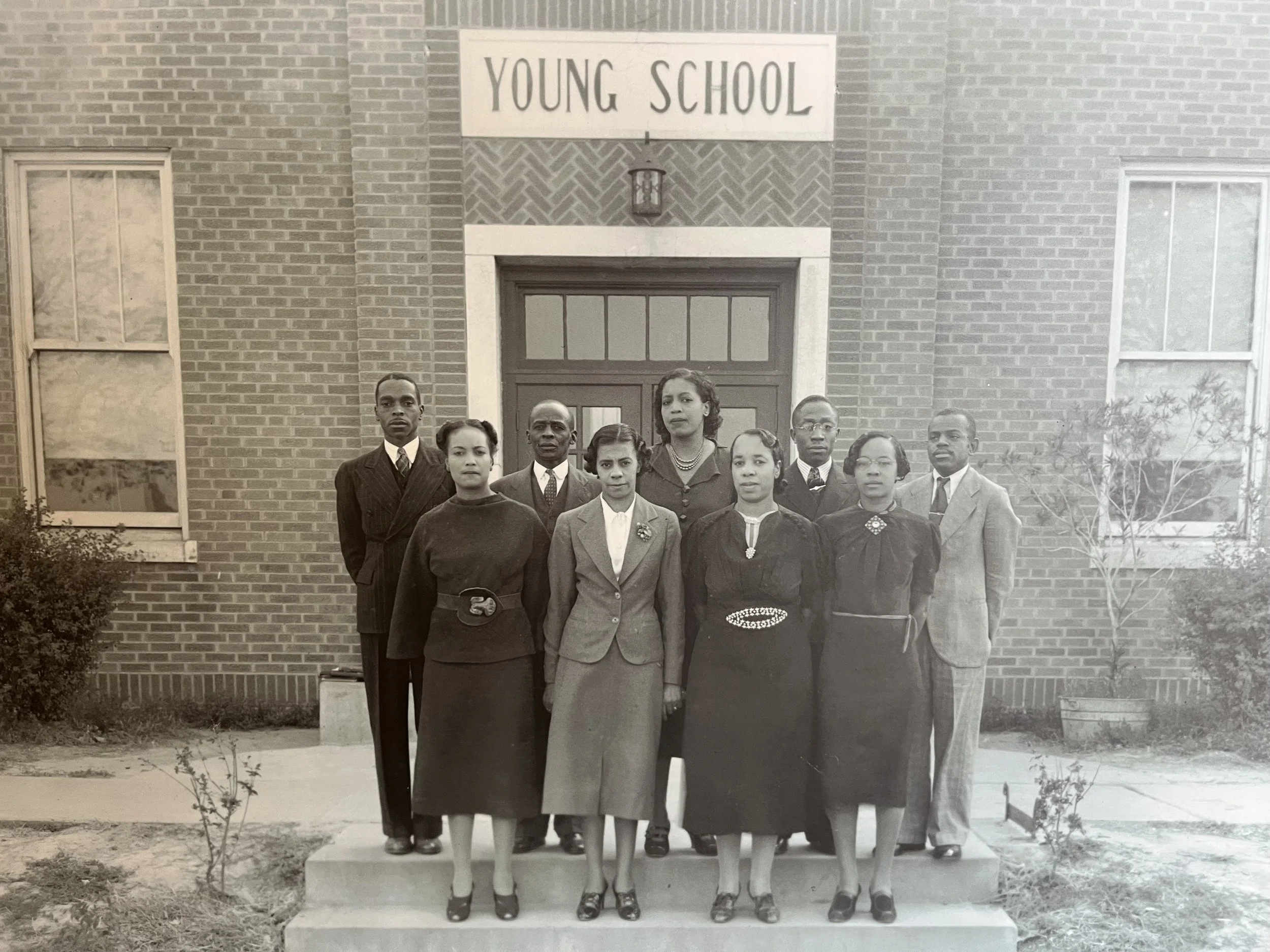

Hiram Young School faculty members convened classes at Hiram Young School for about 20 years, beginning in 1935. Photo courtesy of the Truman Heritage Habitat for Humanity.

Among those then preparing to follow the overland trails west, many either knew or soon learned that Young’s wagons were among the best.

Today, Young’s achievements continue to be honored across Independence but especially at two significant Independence sites: the Historic St. Paul AME Church, founded in 1866 by Young and his wife Matilda, and the former Hiram Young School at 501 N. Dodgion St., where Black students began attending class beginning in 1935.

Remembering, reimagining

The school building, which closed in the years following the 1954 Brown v. Topeka Board of Education Supreme Court decision, which unanimously declared segregation of public schools unconstitutional, today has a new focus.

Since occupying the renovated structure in 2022, Truman Heritage Habitat for Humanity officers have elected to honor Young’s legacy by setting aside one former classroom for use as the small museum. Using grant funds, Habitat officials hired a consultant to reimagine the space.

A consultant submitted renderings suggesting how a small Hiram Young School museum classroom might look if sufficient funds could one day be available. Photo courtesy of Truman Heritage Habitat for Humanity.

Although renderings were completed and alumni video oral histories compiled, sufficient funds to fully outfit the classroom have yet to be attained.

Still, the contemporary reuse of Hiram Young School corresponds with the principal mission of Habitat for Humanity, which builds or rehabilitates affordable homes to help families achieve stability through education and home ownership, Leakey said.

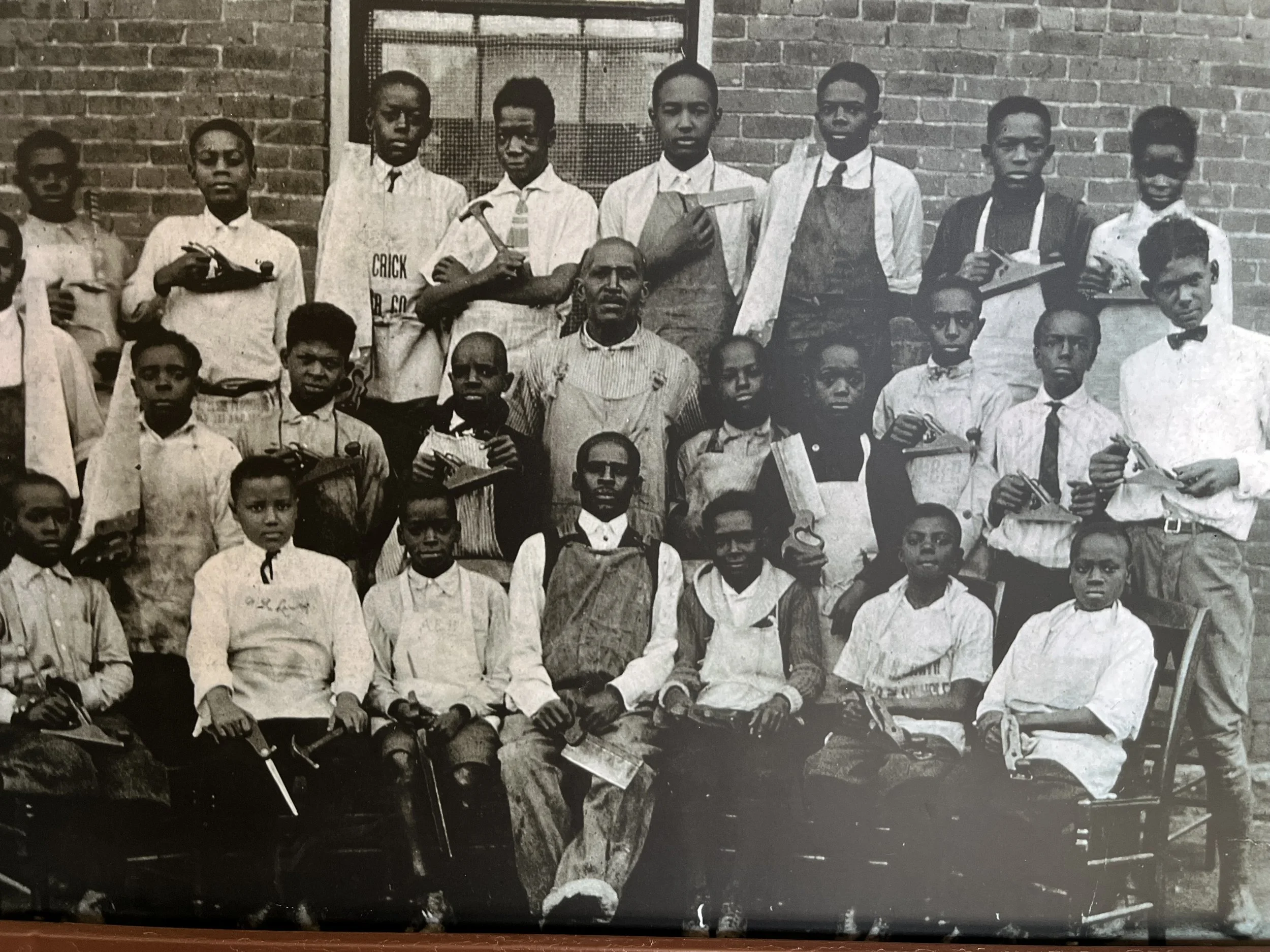

“Through his wagon outfitting business Hiram Young taught other disenfranchised individuals trades that could not only contribute to his own company’s success, but also allow them to develop skills that would give them self-sufficiency and individual empowerment,” she added.

“Today, our focus is helping families achieve financial security through home ownership, which provides them an opportunity to access generational wealth.”

Some Hiram Young School students learned woodworking; as several here can be seen holding hammers, saws, hand planes and swing braces. Photo courtesy of Truman Heritage Habitat for Humanity.

For the families that attended the Young school, Leakey added, many of whose children lived in the predominately African American district known as “The Neck,” that opportunity largely was removed by the 1960s urban renewal program, which was used as an instrument to acquire and demolish private homes there.

While the displaced Black families received compensation for their properties, the options to secure similar housing in Independence were limited through redlining, or the discriminatory practice of denying financial services such as loans or insurance, Leakey said.

The “Neck” district stood south of where the Harry S. Truman Library and Presidential Museum is today, which is just north of U.S. 24 between North Delaware Avenue and North Pleasant Street.

Among the several Young school student alumni who helped stockpile video recollections of their classroom days for Truman Heritage Habitat for Humanity was Alversia Pettigrew, an Independence resident who grew up in “The Neck” and attended the school from 1949 through 1956.

Alversia Pettigrew of Independence has close ties to both Hiram Young School and Historic St. Paul AME Church; she attended classes at the school from 1949 through 1956, and today serves as St. Paul AME Church treasurer. Photo courtesy of the Jackson County Historical Society.

“I think it is so fitting that the Young School has not been torn down and today is helping people of all races with the tools they need,” said Pettigrew, who published a memoir, “Memories of a Neck Child,” in 2000.

“Whenever I walk in I imagine the sounds of the kids I could hear when I was there. I can smell the food in the little lunchroom.

“I didn’t think I would ever get to see the day when I could visit the building and walk the same halls where I used to run,” she added.

If the Young School is one example of how Young’s legacy is being remembered and reimagined in Jackson County today, it’s not the only.

A historic interpretative display devoted to Young is among several installed at the McCoy Park Trail Head at 800 N. Bess Truman Parkway, found in McCoy Park, near West College and North McCoy streets just south of U.S. 24.

There is also Hiram Young Park at 110 S. Noland Road, which features a concrete wagon wheel design as well as a detailed inscription describing Young’s life and work. Dedicated by city officials in 1988, the park sits just south of the Historic St. Paul AME Church, at 200 E. Lexington Avenue, also known as Hiram Young Lane.

Congregation members of Historic St. Paul AME Church in Independence, founded in 1866 by Hiram Young and his wife Matilda, continue to worship together every Sunday. Photo courtesy of the Jackson County Historical Society.

Today, Pastor Everett Fletcher believes Young’s spirit can be experienced inside the church every Sunday.

“I believe the energy of our church leaders stems from how this church was established,” Fletcher said on a recent Sunday.

Fletcher, now in his third year at St. Paul AME, said he was inspired how leaders within the congregation took on leadership roles within the congregation after he was named.

“Sometimes there are people who like to be on the sidelines,” Fletcher said.

“But I had no issues about people stepping up in the leadership, and not all churches have that.

“Hiram Young believed the Independence community needed the presence of a Black church, and I believe that his spirit is still lingering in the members here.”

He also is pleased with how Hiram Young Park is being maintained.

“That shows me that his legacy is still respected in the community,” he said.

Wendy Shay, Independence historic preservation officer, is hoping that, in perhaps two years, the city will receive a grant that will allow the city to hire a consultant who could prepare and submit for St. Paul AME a nomination form arguing for the building being listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

“Recognition is important,” said Shay, adding that the church’s backstory is among the “under-represented” narratives of Independence history.

A “USEFUL LIFE”

Vigorous scholarship into Young’s life has been ongoing.

He was born in Tennessee in 1812 and came to Missouri as an enslaved person, according to a map of African American Historic Sites distributed by the City of Independence.

In 1847, Young, using the money he had made from manufacturing and selling oxen yokes, purchased his freedom, as well as his wife Matilda’s, from George Young of Greene County, Missouri.

By 1850, Young, Matilda, and their infant daughter Amanda had moved from Clay County to Jackson County. Young was working as a carpenter before he, at some point, joined the 11 wagon and carriage makers then operating in Jackson County, according to William Patrick O’Brien, Independence historic preservation officer from 1977 through 1984 and the author of “Merchants of Independence: International Trade on the Santa Fe Trail, 1827-1860,” a study of the Mexican and United States 19th century trade alliances published in 2014.

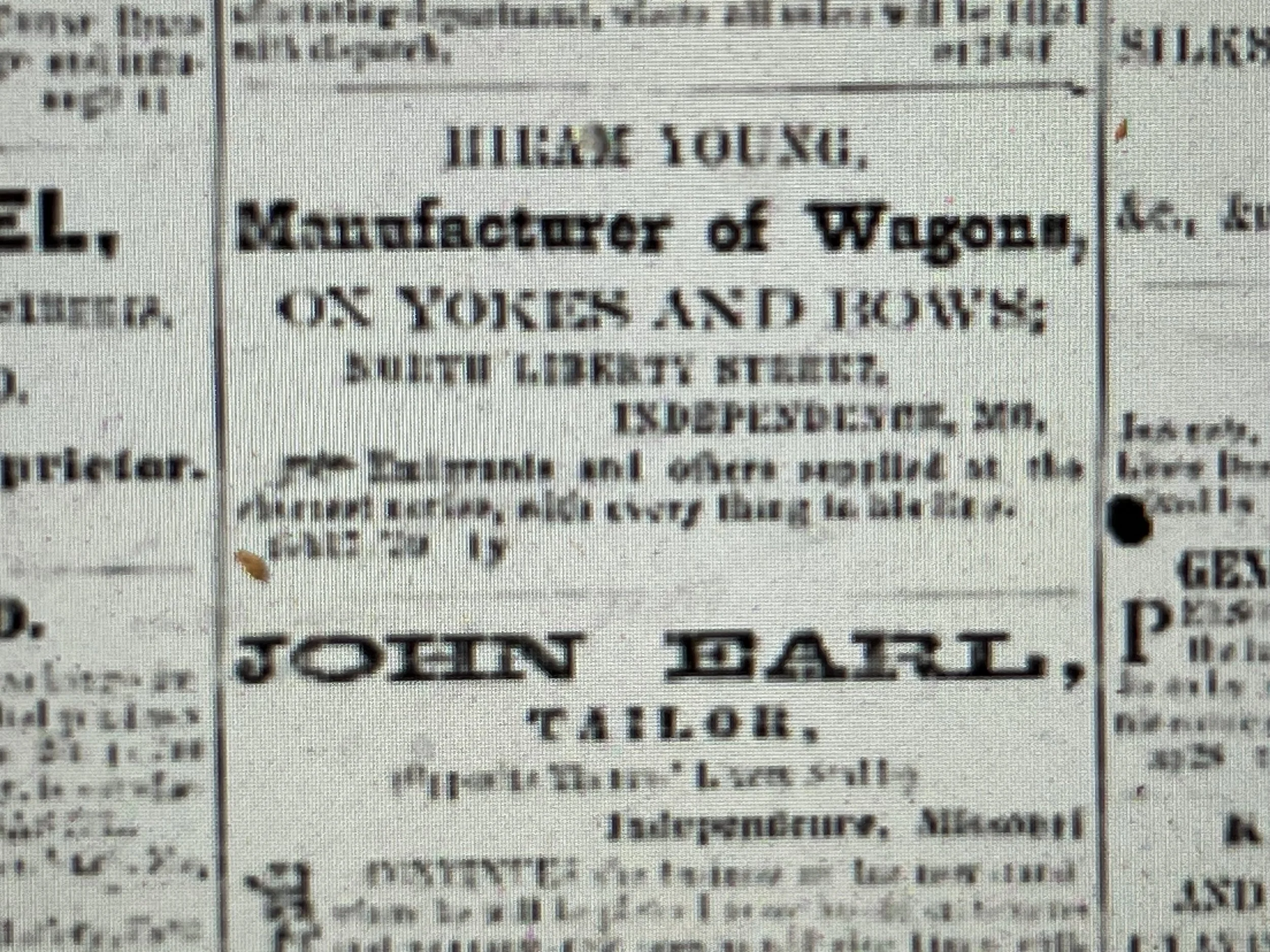

Hiram Young was among the many Independence merchants who advertised; this front page ad in the April 27, 1861 issue of the Independence Daily Evening Gazette likely attracted the attention of overland trail emigrants eager to depart by late spring. Photo courtesy of newspapers.com.

By 1860, O’Brien writes, Young employed between 50 and 60 men at his shop, which turned out between 800 and 900 wagons a year, along with thousands of oxen yokes.

In 1861, Young left Independence for Fort Leavenworth, Kansas in 1861, given tensions generated during the Civil War.

Following the war, Young returned to Independence, where he and his wife established St. Paul AME.

In 1874, Young raised $4,000 to build a two-story brick school for Black students. Standing at the northwest corner of Farmer Street and North Noland Road, the school was named for orator and abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Following Young’s 1882 death - and after leading a “useful life,” according to his Woodlawn Cemetery grave memorial - admirers renamed the school for Young.

Black students received instruction there until the 1935 opening of the new Young School on North Dodgion Street.

Often, the students at the new Young School, among them Pettigrew, did not know who Hiram Young had been, often assuming the words “Young School” simply meant it was a school for children who were, by definition, young.

Young’s legacy only really became known to her and others, Pettigrew said, through their acquaintanceship with Bill and Annette Curtis, both of them scholars of Jackson County history.

“I didn’t know anything about Hiram Young being responsible for the school,” said Pettigrew.

In 1881, Young had filed a claim against the United States seeking compensation for damages to his property by federal troops during the war.

He died the following year.

For more than 20 years, litigation continued, with testimony offered by both military and civilian associates of Young.

Young’s claims were denied in 1903.

But his stock as an authentic historical figure began to rise.

In 1932, the Independence Examiner reprinted the winning entry in the Jackson County Pioneer Essay Contest, sponsored by the Independence Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

As judged by J. Allen Prewitt, former Independence mayor, the top prize of $10 went to Martha Basye for her essay on Hiram Young.

“Although mixed with stereotypes,” Annette Curtis wrote of Basye’s essay in a 2011 research compilation, “it is a valuable addition to written knowledge about Hiram Young.”

Basye, according to Curtis, had interviewed Nathaniel Bush, a principal of the initial Young School, as well as surviving Young acquaintances. Basye’s essay added to the sum of community knowledge about Young but also suggested that interest into the former enslaved person’s story was increasing.

“Just now are people of Independence beginning to realize that a truly great man has lived and worked here in their midst,” Basye wrote.

The new Hiram Young School opened three years later.

“PRETTY TOUGH HISTORY”

In the years following the 1954 Brown v. Board decision through the 1980s, the Independence School District used the Young School building for the instruction of special needs students. Later, the building stood closed before Habitat for Humanity acquired it in 2015.

During the building’s renovation, workers did their best to salvage whatever historic artifacts they could find, Christina Leakey said.

Today, the unfinished museum classroom incorporates a green chalkboard authentic to the time. The chalkboard itself has been framed with wooden trim in part collected from other former classrooms, which helps the museum classroom retain some of the building’s “historic fabric,” Leakey said.

Among the preserved Hiram Young School artifacts is its “master clock,” which ensured classes started and ended in a uniform fashion. Photo courtesy of Truman Heritage Habitat for Humanity.

While the classroom desks displayed are not original to the building, many of them are authentic to the time period.

One especially unique item is a clock - not merely a classroom clock but a “master clock” that synchronized all of the buildings’ clocks, ensuring that bells or alerts that signaled the start or end of individual class sessions were done in a uniform way.

“The largest part of our fundraising was for the building itself; we had to be focused on getting the building completed,” Leakey said.

“The classroom museum has been an adjacent initiative.”

Today, the former Hiram Young School, as used by Truman Heritage Habitat for Humanity, not only serves to instruct families in self-sufficiency and home ownership, Leakey said, but also represents a space for community dialogue about how the realities of its racial legacy continue to evolve.

“A lot of this is pretty tough history,” Leakey said, “and there are still a lot of feelings that are still being processed, and a lot of relationships that still need mending.

“Being able to offer this building supports opportunities for those community conversations.”

Brian Burnes is the former president of the Jackson County Historical Society.