Diary of Police Officer Max Gould Recalls Truman’s Return to Independence

A young Max Gould appears in uniform for civilian defense work as an auxiliary police officer for the City of Independence. He later joined the regular Independence Police in 1949. Image courtesy of John Pritchard.

This month’s E-Journal is based on the diary entries of police officer Max Gould of

Independence, who documented in real time his service on Harry S. Truman’s security

detail. Gould’s work grew into a friendship and influenced his family for generations to

come. This article originally appeared in the summer 2014 JCHS Journal. It is

republished here to add a postscript explaining how Gould’s grandson, John Pritchard,

is continuing his family’s Truman connection in a unique way.

By Brad Pace

Immediately following Dwight D. Eisenhower’s inauguration on Jan. 20, 1953, the 34th

president of the United States, Harry S. Truman, now a private citizen, embarked on a

cross-country train trip to return to his hometown of Independence, Mo.

We will never know for sure what thoughts raced through his mind on that long trip, but

certainly, he had time to reflect on how he might spend the rest of his life as a former

president. Of course, he would not be the first ex-president, but he would be the first

past president in the post-World War II era.

The legendary Franklin Roosevelt had been elected four times before dying in office.

The last president to actually leave office was Herbert Hoover in 1933 – before the

United States had become a nuclear superpower, before the Cold War, before TV. The

world had changed dramatically. This was the atomic age.

Officer Max Winfield Gould

Back in Missouri, a good many people were also wondering exactly how a past U.S.

president would settle into the routine of daily life in Independence, then a town of about

40,000.

A young Max Gould appears in uniform for civilian defense work as an auxiliary police officer for the City of Independence. He later joined the regular Independence Police in 1949. Image courtesy of John Pritchard.

No doubt one of those wondering was 51-year-old Independence policeman

Max Winfield Gould. A native of Independence, Gould started his career in

law enforcement serving in the auxiliary with the Civilian Defense Program

during World War II, and later joined the Independence Police Department

in 1949.

Gould was a quiet man of few, but well-chosen words. He trained in jujitsu

and judo. Not big physically, he was about average size, but tough and wiry.

He was the kind of cop who was a natural at breaking up bar fights and

comfortable being the muscle behind local law and order. His reputation was

known to cause suspects to take off running when “Patrolman Gould”

arrived on the scene. He was also a complex and kind man who would take a person into his home if they

were down on their luck.

Although Truman and Gould travelled in very different orbits, their paths were destined to cross in the

winter of 1953.

Security for the Former President

The end of President Truman’s work in Washington meant new responsibilities for the

Independence police force. There was no permanent federal Secret Service protection

for ex-presidents in 1953. The responsibility to provide security would be shouldered by

state and local law enforcement and was not something to be taken lightly.

Only a few years earlier, in 1950, two Puerto Rican nationalists had attempted to

assassinate Truman while he was staying at Blair House, the presidential guest house.

The resulting gunfight left one of the would-be assassins dead, and the other seriously

injured. One White House policeman was also killed, and two others were wounded.

Anticipating Truman’s return to town, the Independence Police Department devised a

plan to provide guard duty. While most of the patrolmen on the Independence police

applied for this protection detail, Max Gould was one of only three officers initially

chosen. The two others were Mike Westwood and Ted Osborn.

Gould’s initial delight at being selected was tempered when he learned that he was

assigned to the graveyard shift – midnight to 8 a.m. He did not know it at the time, but

this would turn out to be fortuitous.

His late-night shift was not the only thing that would set him apart. Gould would keep

a daily diary to document his duties and interactions with the former President.

Max Winfield Gould reported for guard duty at the Truman home at 219 N. Delaware

Street at 11:45 p.m. on Tuesday, Jan. 20, 1953, the very same day Dwight Eisenhower

was sworn in as the new President of the United States. Gould’s first night on duty was

uneventful since the Trumans were not expected to arrive from the capital until

Thursday, Jan. 22, 1953.

Everyone knew January 22 would be a big day, so Gould was given an extra duty shift that

evening. When he arrived at the Truman home, there were already several hundred

people on the streets surrounding the house. Delaware Street had been blocked off to

traffic from Maple Avenue to Truman Road.

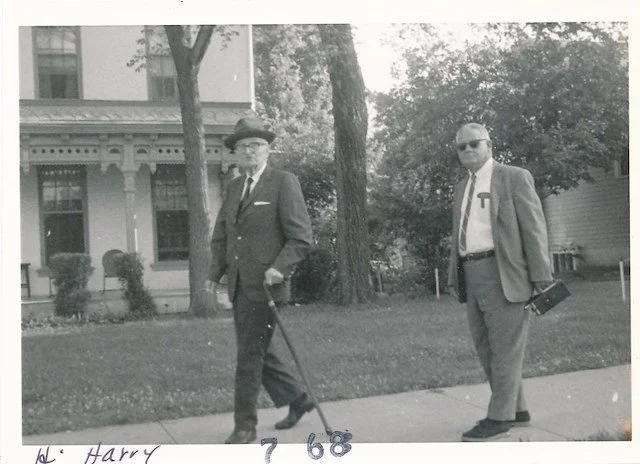

Crowd in front of the Truman home in July 1968, on the occasion of a visit by President Lyndon Johnson. President Truman can be seen standing on the front porch. JCHS Image No. PHM 11620.

Gould helped move the crowd back to clear room for the

newspaper, TV, and radio reporters and cameramen, not to

mention the entire William Chrisman High School Band. The

Truman train was scheduled to arrive at the Missouri Pacific

Depot located about a mile away. Approximately 150 law

enforcement officers added to the large crowd, which had

already overwhelmed the small depot. Between those at the

depot and the others surrounding the Truman home, the total

number of persons present was estimated to have been more

than 10,000.

Gould’s diary records that the evening was cold and blustery with snow covering the ground, but that

everyone was in a “jolly mood.” Gould thought he heard a train whistle and a distant cheering from the

crowd at the depot.

When the procession from the station turned the corner off Maple Avenue from the west and proceeded

onto Delaware Street, a cheer went up from the crowd, and the band started playing. Truman’s car stopped

by the gate in front of his house.

Harry and Bess Truman Return Home

Harry and Bess Truman emerged from the car and were immediately surrounded by

friends and well-wishers. When Truman walked forward into the street to

congratulate the band master for a fine performance, the excited crowd surged.

Police officers struggled to hold back the multitudes and to get the front gate open so

the Trumans could enter the safety and relative calm of their yard. Truman walked

to his front porch and addressed the crowd, saying it was the largest that had ever

welcomed him home, even while he was president. He added that he was glad to be

able to come home for good.

Group of Independence Police officers, Max Gould center. Image courtesy of John Pritchard.

Once Truman had retreated inside the house, Gould and the

other officers were left to deal with the many people in the

crowd who wanted admission. Some were old friends, while

others were just overly curious, but no one was let in. When the

crowd died down a bit, Gould decided to go home and get a little

rest. It had been an exciting and stressful day. But he was still

expected to return in a few hours to begin his regular midnight

to 8 a.m. shift.

When Gould returned a few hours later, he found that heavy traffic was still cruising around the house.

Around 6 a.m., about a half-dozen reporters showed up at the gate on the north side of the Truman home,

where the driveway meets Truman Road. This became known by some of the security officers on duty as

the “old north gate.” Truman had been known in the past to take a walk in the mornings before breakfast.

Nobody knew if he would be continuing this practice. When reporters began asking Gould if Truman would

be coming out, he could honestly say he had no idea. Officer Mike Westwood arrived to relieve Gould at

about 7:40 a.m., and the reporters began pestering him as well. When Gould finally left, there was still no

sign of the ex- president. This would be the pattern for several days until Monday, Jan. 26, 1953, when Gould

would finally have a chance to see Truman.

The midnight shift on January 26 had been uneventful. At a little after 6 a.m., news and cameramen began to

gather at the old north gate. At about 7:15 a.m., the Trumans’ cook arrived by cab, and this prompted the

newsmen to start asking whether the ex-president would be coming out. As usual, Gould replied that he had

no idea. Then at 7:30 a.m. Truman suddenly

Harry S Truman on one of his many morning walks. JCHS Image No. PHS 12007 B.

opened the door and appeared for his much-anticipated

morning walk. Gould’s diary describes that Truman “came out

the back door immaculately dressed, like he just stepped out of

a fashion plate—hat, overcoat, dark gray, blue serge suit

(meaning a twill-weave or worsted fabric), black gloves, black

oxfords, cane.”

“He greeted me with a smile and a cheery good morning.” Gould

then said, “Mr. Truman, I don’t know if I am supposed to accompany you on your walks or not. What are

your wishes on the matter?” Truman replied that “maybe it would be best for me to go with him, and that

personally he would be glad to have me along.”

Gould then warned Truman about the waiting newsmen and photographers.

Truman responded: “I suppose that is one thing we will have to contend with, for a

while at least.”

The ex-president then greeted the newsmen cordially enough, but did not waste any

time with them and headed directly for his walk. When one of the newsmen asked if

they could take some photos, Truman replied that “a good walk would not hurt that

waistline any” and that “I won’t be responsible for any damage to the cameras.”

This unusual group then set off walking towards the Independence Square. The talk

was general until one of the reporters asked a political question. Gould’s diary notes

record that Truman explained to the reporters that he had no intention of commenting

on public affairs, and that he did not want anyone to feel offended if he refused to

answer such questions because there would be no offense intended. He added that

they were still welcome to come along for the walk, as it would probably do them good.

Gould kept to the rear of the procession where he could watch everyone and still hear

most of what was being said. The walk may have been congenial exercise for Truman,

but it was all business for Gould. When the group finally returned to the “old north gate.”

Truman bid the reporters adieu and thanked Gould for a “very pleasant walk.”

Officer Mike Westwood relieved Gould and handed Truman the morning telegrams and

special delivery letters. Gould wrote in his diary, “That was the beginning of our many

walks and a friendship that I shall cherish as long as I live.”

Being on the midnight to 8 a.m. shift meant Gould would typically be on duty for

Truman’s morning walk. He soon began to look forward to Truman’s cheery smile and

“Good morning.”

His diary describes Truman as a “very pleasant and congenial man” with a “wonderful

personality.”

President Truman walking in Independence, Missouri in 1945. Photo courtesy of John M. Friedlander. Harry S. Truman Library.

Many of those Truman encountered on his morning walks would offer a greeting or a

wave. In the early days following Truman’s return to Independence, reporters were

typically waiting to walk with him. They would often ask Gould if there was any way

they could get Truman’s opinion on foreign affairs. Gould had to explain again and

again the former president’s decision not to comment on such matters.

Some journalists just could not resist going beyond general conversation. In such

cases, Gould would single them out and bar them from the walks. As the days wore on,

he could see the reporters lose interest in the actual walking and begin to give up hope

of getting any real newsworthy information.

“Mr. Truman always walks very fast, and it was darned hard for some of them to keep

up, let alone do much talking,” he wrote. Gould found it amusing that when reporters

asked Truman questions, he would answer them in “such a way that they were more

confused than if he hadn’t answered at all.”

Over time the number of reporters on the morning walks dwindled to the point where

sometimes Truman and Gould would be alone. Truman would then talk freely about his

experiences in the White House and the notables he had met.

He described Soviet leader Joseph Stalin as being very intelligent and pleasant to talk

to. He said Stalin would agree to anything while you were talking to him, then do the

opposite.

Gould’s diary entry for Feb. 11, 1953, records that he remarked to Truman that he had

once saw him on television meeting with Gen. Douglas MacArthur. Truman told Gould

that yes, he had gone to see MacArthur and had given him specific instructions, but that

the general failed to carry them out.

“I signed the order relieving him of his command with the approval of the Chiefs of

Staff,” Truman responded.

Gould noted that Truman did not comment further on the subject, and his impression

was that Truman did not like to talk about it.

One of Gould’s main functions was to serve as a gatekeeper to shield Truman from

the many people wanting to see him. A good example occurred on the morning of Feb.

14, 1953, when a Western Union messenger arrived at the north gate with a telegram

for Truman.

The messenger said he had to deliver it in person. Gould smiled because this had

become an old story by now. He explained that all personal interviews needed to be

arranged at Truman’s office in Kansas City. The messenger became upset and said he

had a job to do and that he intended to do it. He said firmly his orders were to deliver

the telegram now and in person, and that if he did not, he would lose his job.

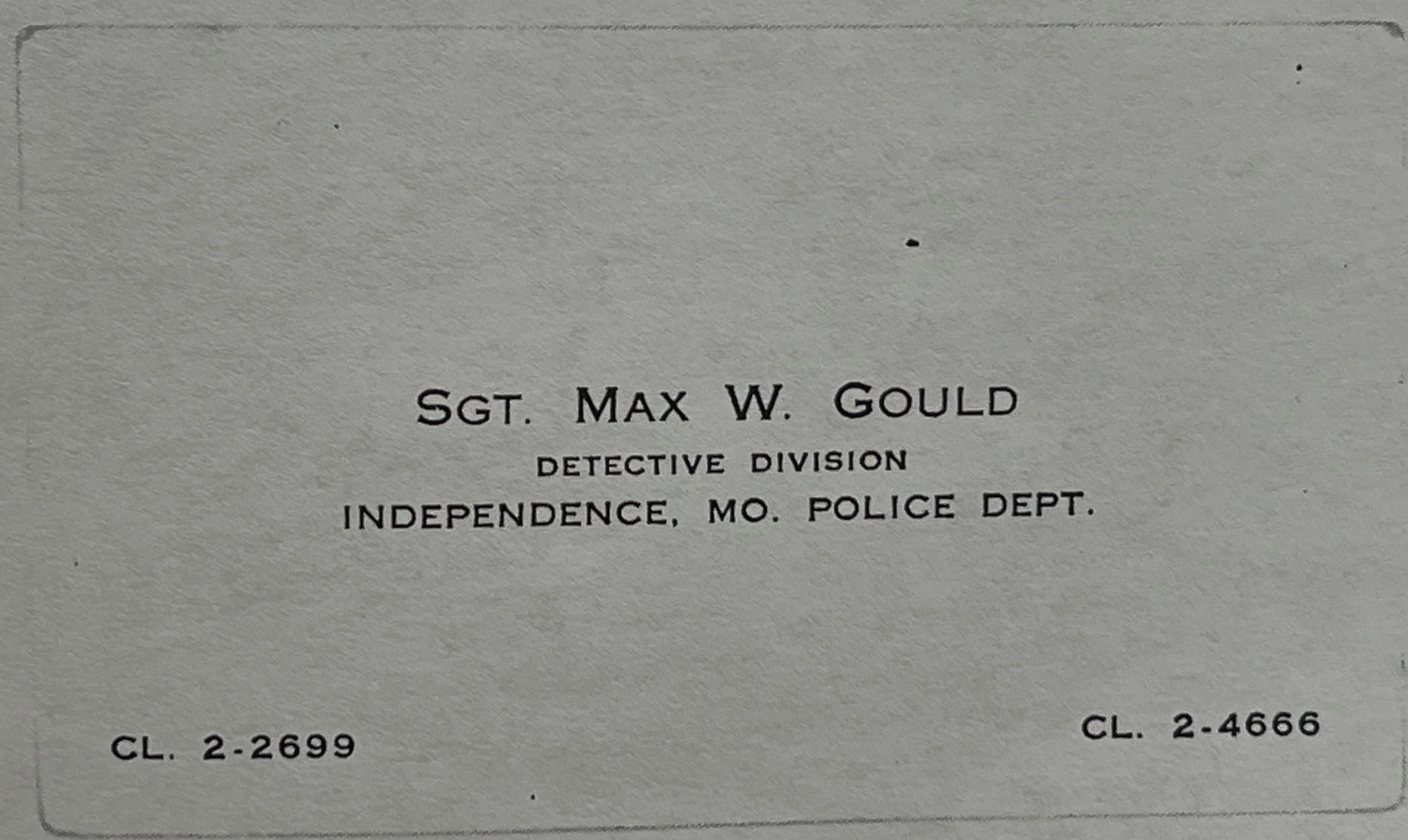

Image courtesy of John Pritchard.

Gould replied: “You know something, you have just lost your

job. Now give me that telegram and get going, or take your

telegram with you, I don’t care which, but get going now.”

The messenger then handed Gould the telegram and made the

usual threats about getting Gould fired. Later, when Gould

delivered the telegram to Truman, he opened and read it, and

then immediately wadded it up and threw it in a waste basket.

Gould thought the telegram must be important, so he went over to it, picked it up, straightened

it out, and handed it back to Truman without reading it, and said, “Hadn’t you better file

this?”

Truman looked at Gould and asked him if he knew what it was. Gould replied he had no

idea. Truman handed it back to Gould and said, “Read it.” When Gould read the

telegram, he saw that it was from a “very reputable organization” in New York City

offering Truman $10,000 for a 30-minute televised speech.

“I have no intentions of capitalizing on the fact that I have been the President of the

United States in any way,” Truman told Gould, who noted in his diary that he doubted if he

could dismiss $10,000 that easily.

Truman was one of the last U.S. presidents to lack a private fortune and the last

president to leave office without any presidential pension.

Fortunately, Truman’s return to Independence was accomplished with few real

security threats. One of the rare incidents, which did occur, was on Saturday, Feb. 7,

1953. At about 1:30 in the morning, a person or persons unknown stopped their car at

the corner of Delaware and Truman Road and fired a gun. Gould thought the sound

was that of a 38 caliber revolver. He immediately called the police station to request

back up. The exterior of the Truman house was later searched, but no bullet holes were

found. Gould concluded that, evidently, it was just someone blowing off steam, but the

event reminded him of the seriousness of his job.

As Truman settled into the role of being an ex-president in a small town, he worked hard

to master the balancing act of leading a normal life while still maintaining the dignity of

his position.

Truman had a deep respect for the office of the presidency and was mindful of the fact

that in a way he would always represent that office, whether he wanted to or not. In public,

his demeanor was cheery and friendly, but never too informal or undignified.

Maintaining this balance was not easy, as shown by an occurrence on Monday, Feb. 9,

1953. During the usual morning walk, Truman and Gould came upon five men standing

by a car. As they drew nearer, one of the men rushed over close to Truman, stuck his

hand out, and hollered, “Hi, Harry.”

Truman stopped, looked at him, and said, “Mr. Truman is the name.” The fellow said

“Yes, I know.”

Truman replied, “Well, use it then,” and walked away.

After he had traveled some distance, Truman explained to Gould that “If there is

anything I hate it is a smart aleck.” He went on to say that he did not mind people he

knew or had known all his life calling him “Harry,” but he felt like, as a former President of

the United States, he was due a “certain amount of respect.”

Gould told Truman that up until that point, he had intended to give people as much

freedom as possible with him as long as they did not get too far out of line, but at the

first sign of belligerence from anyone, he was going to take over and use whatever

means necessary to put them in their place. Truman said that suited him fine.

Truman told Gould he also wanted to give the people a free hand, but that he had a

“perfectly good cane” and that it “could serve many purposes.” Fortunately, there is no

record of Truman ever needing to employ his cane for any purpose beyond its traditional

role.

Gould had noticed Truman’s canes in the past. On one occasion, his diary notes that

Truman was using a new and beautiful cane of highly polished cedar. Truman

explained it was handmade and that he had a pair of them sent to him from a producer

in southern Missouri.

Not an Easy Job

Although it seems clear from his diary notes that Gould enjoyed the honor of being a

security guard for Truman, the job could not have been easy. The hours were

terrible, and the responsibility was great. He would be on duty hour after hour on the

night watch. Most of the time, there would be nothing at all happening, but he would

need to remain vigilant.

Much of his time would have been spent out in the elements—even on cold wintery

nights. When Gould was not at the north gate on Truman Road, or the front gate by

Delaware Street, he could seek shelter in a one-room guard house behind the Truman

home.

The small structure had been built while Truman was president, but was later removed

sometime in the 1950s.

One thing is for certain: he did not spend the cold late-night hours inside the Truman

home. For privacy reasons, that was out of the question. Gould would sometimes keep

himself awake and alert on the overnight shift by sketching drawings, and perhaps also

by making notes for his diary.

The last entry in Officer Gould’s handwritten diary is dated

Monday, Feb. 16, 1953.

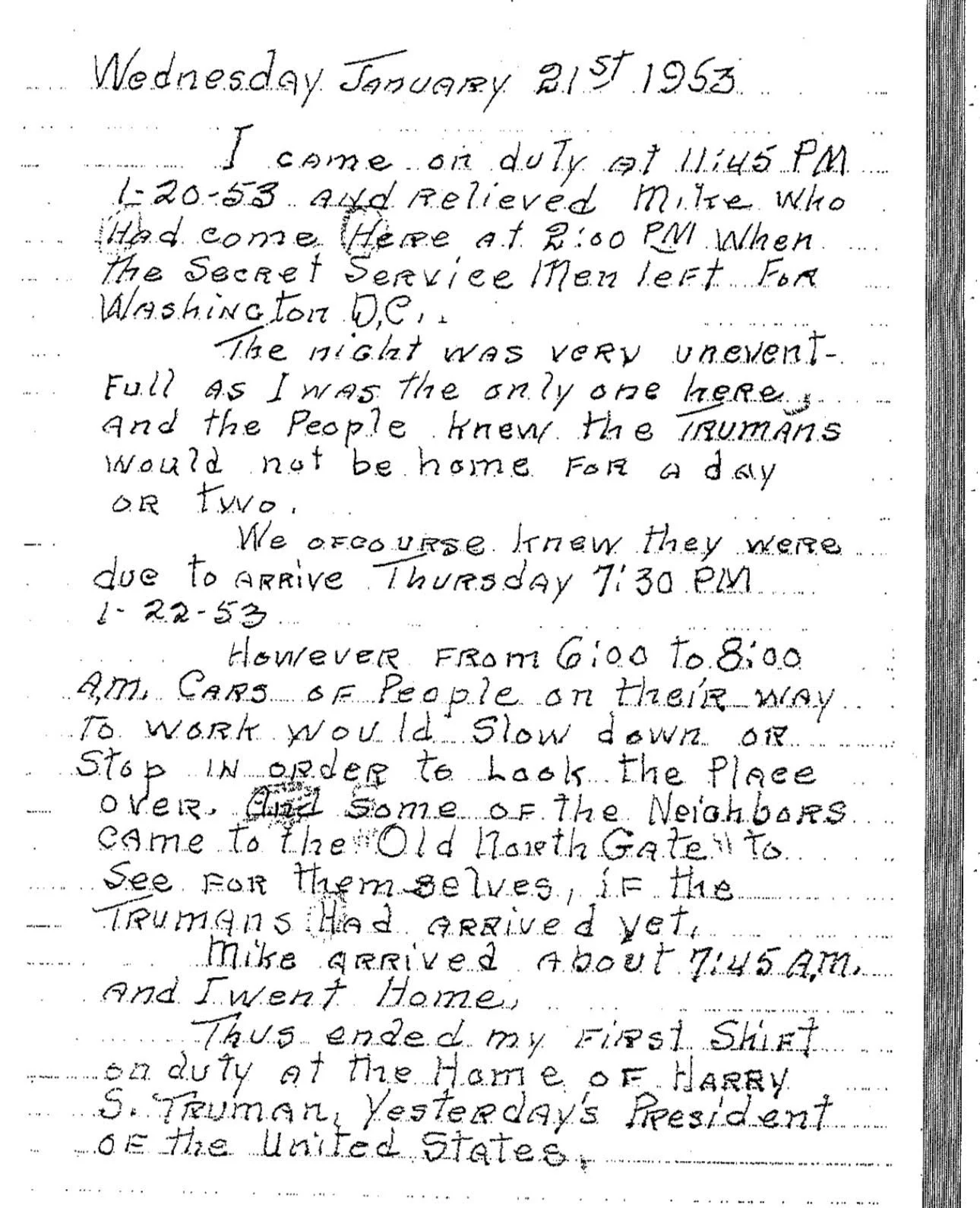

Gould’s journal entry from January 21, 1953.

The diary ends abruptly and without explanation, so it may be

that other pages have been lost to history. It is known that he

soon returned to regular police duty. Fellow officer Mike

Westwood would remain on as bodyguard until Truman’s death

on Dec. 26, 1972.

Gould retired from the Independence police force in 1965. He

had suffered from a variety of health problems for much of his

life and died in 1980 from emphysema and heart disease. In his

later years, he loved telling and retelling stories of his days guarding former

President Truman. He related

to Truman as a friend and neighbor.

In fact, Gould’s two daughters, Dorothy and Maxine, attended Chrisman High School

with Truman’s daughter Margaret, and were in some of the same classes and clubs.

Despite this apparent warmth, Gould and his family were lifelong Republicans.

Nonetheless, his great respect for Truman, the man, remained undiminished.

Toward the end of Gould’s long life, his thoughts must have drifted back to those cold

mornings in the winter of 1953, when he would greet the former leader of the free world

at the “old north gate.”

Postscript

Officer Max Gould’s influence on his family has endured. His two children and four

grandchildren grew up hearing stories of his time guarding Truman, and of their

friendship.

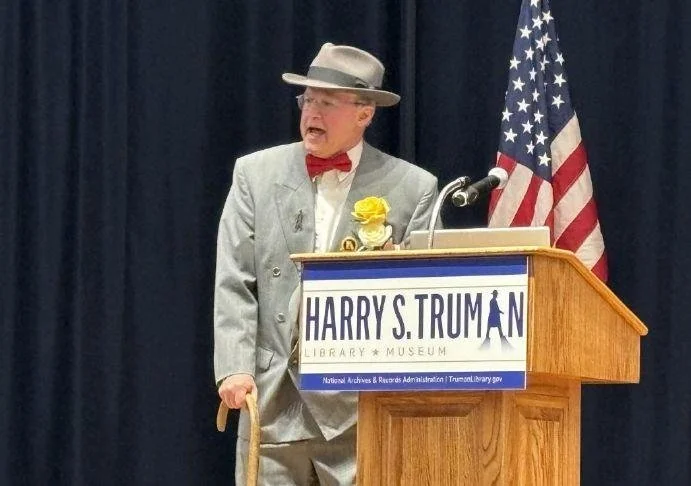

John Pritchard in the courtyard of the Truman Library." Image courtesy of John Pritchard.

One of Gould’s grandsons, Independence native John Pritchard, is

continuing the family’s Truman connection in a unique way.

It all started in 2022, when Pritchard’s wife asked him to appear at a gala

luncheon for the Bess Truman Scholarship fund, dressed as the former

president. Pritchard was reluctant at first, thinking he didn’t look much like

Truman. But after donning a double- breasted business suit, accessorized

with bow tie, round glasses, fedora hat, and cane, his appearance was

transformed.

Passing the Torch

For many years, the job of impersonating Harry Truman had been filled by Niel Johson,

a history professor who had served as an archivist and oral historian at the Truman

Library. Johnson also published a book on Truman, “Power, Money and Women: Words

to the Wise from Harry S. Truman.” Johnson’s re-enacting was very highly regarded for

John Pritchard appeared in 2022 at an event for the “Bess Truman Tea" event. Photograph by Mike Genet.

its historical accuracy. But in 2015, at age 84, he announced his

intention to retire from the role.

After Pritchard’s successful experience at the gala luncheon, he

decided to fill the need following Johnson’s retirement, and take

up the challenge of impersonating Truman at events around the

Kansas City metro area.

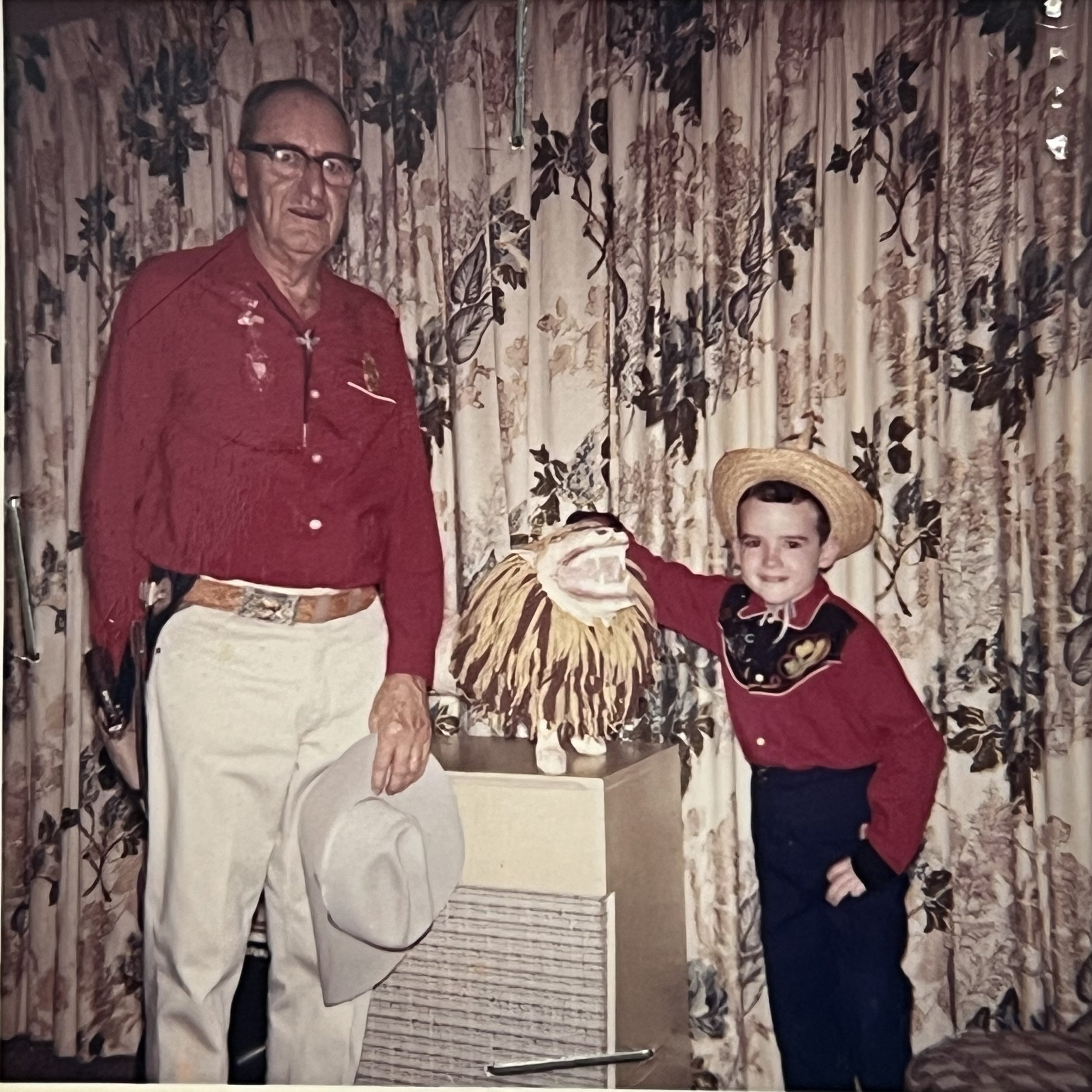

He may not have been a professor and archivist, but he had a lifelong interest in

Truman –- something not surprising given his relation to Max Gould. When Pritchard

was only six years old, Gould had even introduced him to Truman at a police rodeo.

Gould and six year old John Pritchard ready for a police rodeo event in 1964, where Pritchard was introduced to the former president, and shook his hand. Image courtesy of John Pritchard.

When Harry S. Truman passed away on December 26, 1972,

Pritchard (then age 15) decided to take the family’s Super 8

film camera and film as much of the funeral as possible. Being a

presidential funeral, it involved several areas across

Independence. He filmed at the Carson Funeral Home, where

the body was held, at the Truman Library to witness a 21-gun

salute, and even at the nearby Mill Creek Park, as President

Richard Nixon and First Lady Pat Nixon departed by Marine

One helicopter.

Travelling around town that day filming, Pritchard felt he was

taking part in history.

Still a Part of History

Seeing double, John Pritchard appears with Niel Johnson. Image courtesy of John Pritchard.

Now, more than 50 years since Truman’s funeral, Pritchard’s re-

enactments are helping others to appreciate a bit of presidential

history. He says he enjoys talking to people and that, as a native

of Independence, he wants to promote its history.

“The aspect of Harry Truman I am trying to recreate is his life

after he came back to Independence. That’s what I heard about

growing up,” Pritchard explained. He says that although he is

not a historian, he is an expert on his grandfather’s experience.

“What I like to talk about, and people really light up, is when I tell my grandpa’s story,” said Pritchard.

He says that Truman was known for his walks around town, and that “as long as I am

able, I will try to walk fast, and to remind people of that time when you could go out to

the Square in Independence and see a former president high-tailing it down the

sidewalk.”

Image courtesy of John Pritchard.

Pritchard has appeared at events for the Truman Library, the

Independence Square Association, the Santa-Cali-Gon festival,

parades, and many others. He says that when he does an event,

there is always one or two people that he really connects with.

Various reenactments are already planned for 2026, including at

the Truman Library for Presidents’ Day and Truman’s birthday.

Although Harry Truman passed away 53 years ago, the next time

you attend a community event and spot a distinguished-looking gentleman sporting a double-breasted

suit, bow tie, and fedora hat, you just might be seeing John Pritchard keeping alive the memory of our

nation’s 33rd president.

Brad Pace is a current board member and past president of the JCHS. He is a frequent writer on historical subjects.