Jackson County Remembers V-J Day on 80th Anniversary

An end of the war extra edition of The Kansas City Star is sold to a U.S. Navy sailor in Liberty, Mo. Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Mo.

When President Harry Truman announced the unconditional surrender of Japan on August 14, 1945, it was time to celebrate.

Jackson County residents reacted in a fashion similar to what was seen in communities large and small across the country. The scenes of huge crowds in New York’s Time Square were repeated, on a smaller scale, in Kansas City and Independence,

One difference in Jackson County, of course, is that President Truman and his family happened to live in Independence. Many local residents knew individual Truman family members as a friend, or neighbor, or the occasional customer at the Maple Avenue and Union Street gas station. As described here, in this month’s E-Journal, Independence Examiner journalist Sue Gentry, a friend of Bess Truman, witnessed the president’s White House announcement and quickly transmitted her story back to Independence.

But other than that, the Jackson County celebrations - just like many across the country - included impromptu parades, the throwing of pillow feathers from high windows, and the indiscriminate hugging of strangers.

To Jackson County residents of 2025, the scenes recall the recent Union Station victory celebrations following Super Bowl and World Series victories.

But to compare the end of World War II to professional sports championships trivializes what was being celebrated in 1945 - the vast and palpable relief that the war was over and the soldiers and sailors soon would be returning home.

Eighty years ago, nobody knew of an atomic bomb.

They just knew - beginning on May 8, when Truman had declared Victory in Europe - that a traditional invasion of the Japanese home islands was being planned, with the projected number of casualties too terrible to contemplate.

Accordingly, the widespread feeling in Jackson County, as Brad Pace writes, had been one of “dread.”

By Brad Pace

May 8, 1945, one day following Germany’s surrender to the Allies in Reims, France, is recognized as Victory in Europe Day, V-E Day. The celebrations that spontaneously erupted across Jackson County and the nation that day were haunted by the knowledge that the job was only half done. This feeling was echoed by President Harry Truman, who in his V-E Day speech reminded his listeners of the work needed to “finish the war.”

Countdown to Victory

All through the summer of 1945, the fighting and dying continued in the Pacific. America’s successful island-hopping campaign had pushed the Japanese back to Okinawa, part of the Ryukyu Islands, the southernmost and westernmost prefectures of Japan.

Taking little notice of V-E Day, the brutal fighting on Okinawa carried on through the second half of June, resulting in more than 12,000 U.S. Marines killed or missing, and a far greater number of Japanese casualties. Americans following news of the battle understood it was a grim forecast of the even greater violence to be expected in the planned invasion of the Japanese main islands.

With military personnel being transferred directly from Europe to the Pacific Theater, and others being trained stateside for imminent deployment, a sense of dread prevailed.

Then on Aug. 6, 1945, Americans were astounded to learn that a new type of weapon, an atomic bomb, had been used to destroy the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Later that day President Truman recorded a press release explaining that the new bomb was a “harnessing of the basic power of the universe.” Expectations quickly rose that the war might end soon after all.

Aug. 8, 1945 brought more crushing news to the Japanese people, when the Soviet Union declared war on Japan. But still there was no surrender.

On August 9 a second atomic bomb was dropped, destroying the city of Nagasaki.

Public sentiment at this point was that Japan must be reaching its breaking point, and that capitulation could come at any moment.

The headline on page one of The Kansas City Star newspaper for August 10 heralded in all-cap, bold typeface, “ALLIES GET TOKYO PEACE OFFER.” Japan would surrender, but only if the emperor could retain his rights as sovereign. While Allied leaders studied the merits and meaning of the Japanese proposal, President Truman clarified that no official peace offer had been received, and that the war was continuing.

Kansas City radio station WDAF announced it would immediately interrupt all programming to report any developments.

August 11 brought news that the Allies had replied to the Japanese surrender offer with a counter which would allow the emperor to remain, but on the condition that he be subject to orders of the supreme Allied commander. It was now up to Japan to reply to this counteroffer.

By Monday Aug. 13, Jackson County was on edge with anticipation. The Kansas City Times (Kansas City’s morning newspaper), reported that the continuing delays might mean the Japanese leadership was split over the role of the emperor, which could lead to a resumption of “Atomic Bombing.”

Japan Agrees to Terms

On Tuesday, Aug. 14, 1945, a Tokyo radio broadcast (12:50 a.m. Kansas City time), reported that an imperial message accepting the Allies’ surrender terms was expected soon. Although official confirmation had yet to materialize, isolated celebrations began to unfold across the country.

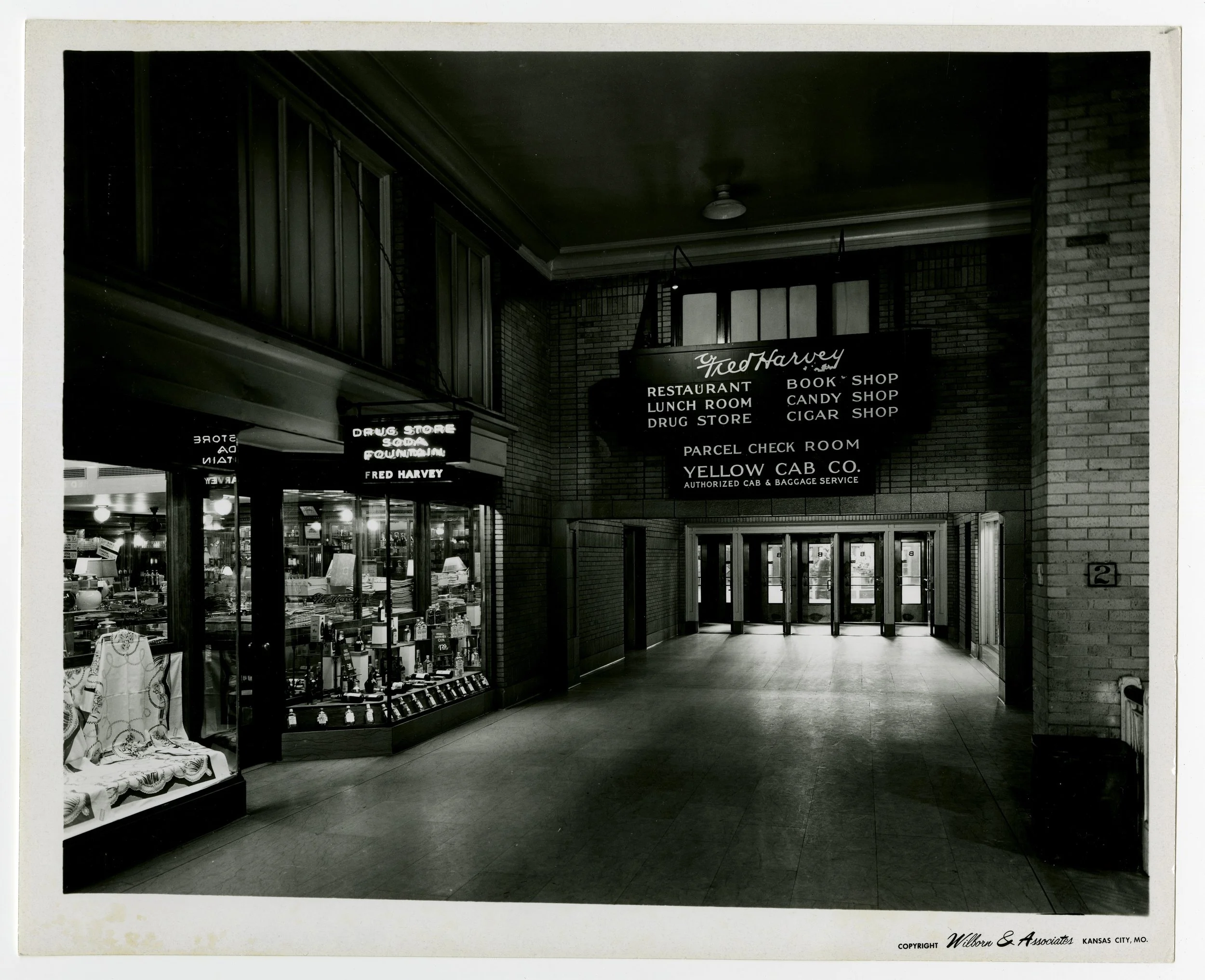

While most of Jackson County waited calmly that Tuesday morning, some were intent on celebrating, official V-J Day or no. Roughly 300 people, many of them teenagers, gathered at the Holy Rosary Church, 911 East Missouri Ave., Kansas City, when church bells began tolling. Following morning prayers, hundreds began a spontaneous parade to the Union Station, blowing horns, beating drums and singing. The manager of Union Station’s Fred Harvey Restaurant reported that the talk that morning was of a possible end to the war, and of servicemen coming home.

Print newspapers struggled to keep up with the fast pace of events. The Kansas City Star published that afternoon carried the disappointing banner, “WHITE HOUSE ANNOUNCES DELAY,” and explained again that Japan’s official reply to the surrender terms had not yet been received.

President Truman announces the surrender of Japan. First Lady Bess Truman is seated on the couch, to the left, second from the end. Harry S. Truman Library and Museum, Harris & Ewing, accession number 59-1542.

Meanwhile as President Truman waited nervously inside the White House, servicemen and civilians danced in a serpentine conga line just outside the front gate—their enthusiasm boiling over despite the uncertainty.

After a long day of suspense, at 7 p.m. Washington time (6 p.m. Kansas City time), Truman was finally able to announce the news that the whole world was waiting for, Japan had surrendered unconditionally. The Allied armed forces were ordered to cease offensive operations. General MacArthur was appointed Supreme Allied Commander to accept the formal surrender at a date soon to be set. Only then would V-J Day (Victory Over Japan) be officially proclaimed.

The Independence Examiner Gets the Scoop

The Japanese surrender was the number one story all over the world, and Sue Gentry, City Editor for the Independence Examiner, was among the very first to report the news.

As luck would have it, Gentry (who would later serve as president of the Jackson County Historical Society), was at that time in Washington D.C. vacationing with a friend. She had been listening to reports on the radio and thought it looked increasingly likely the Japanese might “throw in the towel” that very day.

Being from Independence, and in the news business, Gentry was acquainted with the Trumans. She remembered that Bess Truman had once told her that she might call on her if she was ever in Washington. Thinking this would be the best possible time to accept the offer, she placed a phone call to the White House, gave her name and address, and asked to speak with Mrs. Truman.

Sue Gentry was present with the press pool in the Oval Office when President Truman announced the Japanese surrender. She served as Jackson County Historical Society president 1974 to 1976. Jackson County Historical Society Image No. PHS 22575.

Eventually the First Lady was joined to the call. Sue anxiously explained that she would love to attend the president’s upcoming press conference. Mrs. Truman said she would get her a press card. Sure enough, a few hours later Gentry received a call from the White House asking her to come to the northeast entrance.

Dashing down Connecticut Avenue, she hailed a taxi and tried to hide her excitement when she calmly announced to the driver, “White House, please, northeast entrance.”

Upon arrival Gentry gave her name and address to the guards, and was let into the building, which was just then getting its first coat of fresh paint since Pearl Harbor. Once inside she was thoroughly questioned, fingerprinted, and granted a White House grounds pass which admitted her to the press room.

When she reached the lobby where the press was gathered, Gentry found the reporters looking “tired, hollow-eyed, and hungry, waiting for the story they knew might break at any moment.” Soon Mrs. Truman’s personal secretary came into the pressroom, and told Sue that the First Lady had asked if she would like to come up to her suite, if she was not afraid of missing something.

Gentry could not resist the invitation, and was hustled through corridors, past the East Room, Blue Room and State Dining Rooms. When Mrs. Truman spotted her, she invited her to have tea on the south portico. After tea, cake and punch, Mrs. Truman suggested she take a few extra pieces of cake with her back to the pressroom, which she did.

On her way back Sue was spotted by the president, who was being closely followed by Mike, Margaret Truman’s Irish Setter. The president stopped and shook her hand. After a short chat, Truman showed her to his offices, where she met several of his longtime staff members, before finally returning to the pressroom.

Then at about 7 p.m. the group of waiting journalists was ushered into the president’s office. Everyone was tense as Mr. Truman read the message of surrender from the Japanese government.

After a moment of rejoicing, the newsmen rushed off to find a phone to call their papers. With newsreels and cameras still clicking, Sue stayed after the announcement and shook the president’s hand again. She described him as “jubilant.” Almost all the cabinet was present. From the president’s office she could hear the joyous sounds of celebrations going on in front of the White House. The president and Mrs. Truman then walked out on the White House lawn to acknowledge the crowd and were given a great ovation.

Gentry then arranged with Truman’s executive assistant, Rose Conway, from Kansas City, to use her typewriter to type a report for The Examiner. She then walked two-and-a-half blocks from the White House to the nearest Western Union office to submit her news story. The streets were ankle deep in paper, and filled with a “surging joy-mad mob.”

A Dozen New Year’s Eves Rolled into One

As the big news was quickly spread throughout Jackson County by radio and word of mouth, thousands of people instinctively headed to downtown Kansas City, for what has been described as the biggest night downtown Kansas City ever had.

Downtown Kansas City on the evening of August 14, 1945, shortly after Japan’s surrender. Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Mo.

A long line of cars, bumper to bumper, many decorated with flags, slowly snaked into the city center. Revelers on the curbs encouraged drivers to honk their horns, resulting in a continuous cacophony of honking.

It was gridlock in the streets and on the sidewalks. People appeared out of nowhere, waiving flags, beating pots and pans, and generally hooping and hollering. Hawkers worked the crowd selling party favors such as tin horns, paper hats and leis.

What appeared to be confetti began falling like a snowstorm from the upper floors of the Hotel Muehlebach, 200 W. 12th St., and from just across the street at the Phillips Hotel. Except with no confetti handy, revelers had “liberated” the feathers from any available hotel pillow. In 1945, before air-conditioning was commonly available, windows in commercial buildings opened—even in skyscrapers. So out the windows the feathers were tossed. When the supply of feathers was exhausted, people turned to pouring water out the windows. Those celebrating below were treated to a shower.

In the lobby of the Hotel Muehlebach two U.S. Army army nurses just back from Europe refused to believe the surrender could be real, and offered kisses to a fellow hotel guest if he could provide confirmation. In short order he was able to take collection on the spot.

A Marine near Twelfth Street and Baltimore Avenue was heard to say, “Guadalcanal was never like this.” An Army private in the throng kept repeating how much he loved America, democracy, and the whole world.

Staff Sgt. Samuel Kennedy of Greenwood, Arkansas, was treated to a well-earned “victory kiss” from Miss June West, 2332 Spruce Ave., Kansas City. Like many of those in downtown that night Kennedy was travelling through Kansas City on his way home. He had just returned from Europe, where he had been held prisoner by the Germans for nine months. A happy Kennedy exclaimed how friendly Kansas City was that night.

An end of the war extra edition of The Kansas City Star is sold to a U.S. Navy sailor in Liberty, Mo. Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Mo.

As the throng continued to grow, police blocked off McGee Street to 11th and 13th streets.

At about 8 p.m. several boys were evicted from a canopied repair scaffold on the north side of the Hotel Muehelbach. The canopy was near collapse while the boys jumped on it like a trampoline.

Near 12th and Main streets, a parade of tractors and manure spreaders inched along. The lead driver bragged to the crowd that farmers had also helped to win the war. The tractors were loaded with merrymakers, and one of the manure spreaders featured hanging effigies of Hitler, Mussolini and Hirohito.

In what was described as the Battle of 12th Street, a crowd of thousands spent eight hours celebrating what seemed like a dozen New Year’s Eves in one.

Servicemen’s information booth at Kansas City Union Station. Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Mo.

With crowds growing ever more wild, and jammed shoulder-to-shoulder, by 10 p.m. the Muehlebach closed its grill and moved its furnishings out of the lobby. By midnight it was reported that a bonfire, fed by boxes and wooden crates, was burning brightly in the intersection of 12th Street and Grand Avenue.

Celebrations were not limited to the downtown business district. Union Station remained packed throughout the evening, its floors littered with paper streamers, confetti and colored ribbons. Noise from the celebration was reportedly so loud that the train announcers could not be heard. A line of about 200 dancers snaked their way through the station’s long waiting room. Couples square-danced under the station clock. Many added to the din with improvised noisemakers, from cow bells to pots and pans.

War bond booth at Kansas City Union Station. Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Mo.

All across Kansas City people reacted to the news of victory. At 51st and Main streets, children wearing military caps formed a parade.

A woman hopped off a trolley at 67th Street and Prospect Avenue, and hurried home to tell her waiting daughter that her daddy could finally come home.

Although the crowds were joyous and good-natured, Kansas City Mayor John B. Gage announced on the radio that all taverns and bars must close, and not reopen until 7 p.m. the following day, Wednesday, August 15. The thousands of people who milled the streets sharing kisses and partying, did so mostly without liquid encouragement.

News of the Japanese surrender prompted Kansas City Mayor John B. Gage to order the closure of taverns and bars, and later all non-essential businesses. Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Mo.

Bars may have been closed, but churches were open. Houses of worship of all denominations were packed with those giving thanks. Their loved ones serving overseas were now safe.

The President’s Hometown Lets Loose

In Independence the Japanese surrender was announced by a series of short blasts from the whistle on the municipal power plant—today the Roger T. Sermon Community Center at 201 N. Dodgion St.

At 8 p.m. (about two hours after the news broke), a prearranged community thanksgiving service attended by a crowd estimated to have been as large as 5,000 was held on the south side of the town square, which had been roped off. The program was the largest outdoor religious service ever held in Independence, and was broadcast fully by KMBC radio. Loudspeakers were used so the service could be heard on all corners of the square, despite the sounds of honking horns heard from surrounding streets. Independence Mayor Roger T. Sermon said he was sure President Truman wished he could be present. By the time the service had ended thousands more people had arrived.

Independence Mayor Roger T. Sermon in front of the grocery store he operated with business partner Powell Cook. Sermon was mayor of Independence 1924 to 1950. Jackson County Historical Society Image No. PHL 18583 E.

After the religious service concluded, the square was invaded by hundreds of honking cars which jammed the streets, making circles around the courthouse at the center of the square, turning right at each corner, a local custom known as “winding the clock.” Citizens climbed on the bumper-to-bumper cars, some waving flags or throwing confetti.

“People ran from their homes to shout the news to their neighbors.” Many had been in the midst of dinner when news of the surrender arrived. They dropped their food and joined the crowds in the streets.

Police Chief Hal Phillips sized up the situation on the town square by saying, “It’s a lot of noise, and there’s no harm in that.”

Walter Johnson, manager of the Woolworth store on the east side of the square, said upon hearing the loud celebrations, “That’s the sweetest noise I ever heard.” His son was serving in the Pacific.

Discernable above all the din was the continuous chiming of the courthouse bell. One of the bell ringers was the building custodian, Everett Miller, who had helped ring the very same bell 27 years earlier at the end of the First World War. Unfortunately, the vigorous tolling of the bell ended after about 45 minutes when the pull-rope broke.

A few blocks away at the summer White House, 219 N. Delaware St., the president’s daughter Margaret Truman was home, and told reporters she was thrilled.

As in Kansas City, all Independence taverns and places that sold beer or liquor were ordered closed. A separate order from the sheriff’s office was directed to such establishments county-wide.

Mayor Roger T. Sermon announced that August 15 would be a holiday and urged all businesses to close so that “everyone may take part in celebrating the great victory.”

The Morning After

When the sun rose on the morning of Wednesday, August 15, signs of the previous night’s revelry were everywhere, but Kansas City Police Chief Richard R. Foster said there was practically no property damage. The most obvious destruction was to the hotel pillows whose feathers has been “liberated.” Independence police reported only one arrest on the evening of the 14th, for drunken driving.

Kansas City Mayor Gage’s order Tuesday evening closing taverns and liquor outlets was extended to all day Wednesday, August 15, and expanded to include shops, grocery stores, and restaurants. President Truman announced a federal holiday for the 15th and the 16th, so there was no regular mail delivery. Jackson County offices, including the courthouses, were closed on the 15th. The Kansas City Board of Trade was also closed.

In the metro area banks were among the very few establishments which continued to operate. With most businesses closed many people elected to sleep late, recovering from the big party. Kansas City, Kansas was said to be as quiet as a Sunday morning. In Independence it was also quiet—like the morning after New Year’s Eve. As a writer for The Independence Examiner observed, “the long awaited news of surrender had come, we had celebrated. Today we are happy and resting.”

All the merrymaking Tuesday evening caused people to wake up on Wednesday with an appetite. But with almost all grocery stores, drug stores and restaurants closed there were few dining options. It was estimated that fewer than a dozen restaurants were open in all the Kansas City downtown area.

Long lines formed at the Muehlebach Grill, which opened at noon on Wednesday to help out. Most of the large hotels had enough food to last through the day, but could not offer their regular menu service.

Word of any available food travelled fast. Drawn by a window sign advertising scrambled eggs for twenty-five cents, a crowd of mostly out-of-towners queued in line early Wednesday morning at the Pink Kitchen, Ninth and Cherry streets in Kansas City. Some in line reported they had hunted for three hours before finding a place to eat.

At 7 a.m. there were already 75 to 100 customers at the Harvey House Restaurant at Union Station. The supply of meat was soon exhausted, so the Fred Harvey breakfast plates were without the usual bacon, sausage and ham. But patrons were not heard to complain, feeling lucky to get anything at all. It was estimated that over 25,000 meals were served at Union Station on Wednesday the 15th, when the usual number would have been around 9,000.

Long lines formed at Union Station’s Harvey House on the morning after the victory celebrations. It was one of the few restaurants which remained open despite the mayor’s closure order. Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Mo.

About 2,200 meals were served at the Service Men’s Club, 15 E. Pershing Road, while another 1,250 people were fed at the U.S.O. club on Main Street.

Those fortunate to be members of the Kansas City Club, at Thirteenth Street and Baltimore Avenue, were able to be served in its dining room.

The food clamor resulted in plenty of complaints to City Hall. The City Manager for Kansas City, L. P. Cookingham, responded that the city had nothing to do with the closing of food outlets Tuesday night (August 14), explaining that it had only prohibited liquor sales. But he then added that all businesses were requested to remain closed on Wednesday the 15th, except for essential services.

City Manager for Kansas City, L.P. Cookingham, fielded complaints arising from the mayor’s closure orders. Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Mo.

Waiting for V-J Day

While news of the Japanese capitulation had brought universal relief, Jackson Countians were left wondering exactly when and how the formal surrender would occur. Everyone was anxious for the end of the war to be “official.”

President Truman had made it clear that V-J Day would not be proclaimed until the documents of surrender were formally signed.

While the waiting continued, Truman called on churches across America to mark the coming Sunday, August 19, 1945, as a day of national prayer.

Churches in Independence went “all-out” to comply with the president’s wishes . Typical was the Memorial Methodist Church, which offered a morning service focused on giving thanks, and then an evening service on the subject of “Post-War Conditions.”

Metro area churches reported record attendance, their pews packed with returned soldiers and sailors, and the wives, sweethearts and families of those still serving overseas. Pastors spoke of the coming era of peace, reconstruction, forgiveness, and the new Atomic Age.

Meanwhile, there was growing fear of unemployment as war factories announced plans to close. In the immediate wake of the surrender all production contracts were cancelled for the North American Aviation plant in the Fairfax district of Kansas City, Kansas, which made the famous B-25 bomber. The news was similar at the war battery factory at 6300 St. John Ave., Kansas City, Missouri.

Pratt and Whitney aviation engine plant near 95th Street and Troost Avenue in Kansas City. Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Mo.

On August 21, it was announced that the Pratt and Whitney aviation engine plant near 95th Street and Troost Avenue would close effective immediately, with its 17,000 employees dismissed that very day.

The huge Lake City Ordinance plant in eastern Jackson County received orders on August 29 to immediately cease all manufacturing, with 2,800 employees to be released within six weeks. Remington Arms Company, which operated the plant for the government, placed a full-page advertisement in The Examiner on August 31, to give heartfelt thanks to the workers who had produced 5,500,000 rounds of ammunition during the war. At its peak of operation in 1943 the plant employed over 20,000 men and women.

Not surprisingly, it was reported on August 21 that roughly twice the typical number of applicants had been showing up at the United States Employment Service office at 1411 Walnut St. in Kansas City.

Gradually news trickled in about the plans for V-J Day. On August 23, 1945, Gen. Douglas MacArthur announced that the official surrender would take place on board the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay (not at the emperor’s palace as had been rumored).

Two Independence men were expected to witness the surrender ceremony on the USS Missouri. One was John C. Truman, seaman first class (a nephew of President Truman), and the other was Harold E. Wallace, electrician’s mate first class. According to local relatives both men had just recently written letters home talking about the atom bomb and expressing hopes for the end of the war.

Even without an official end to the war, signs of a return to peacetime life began to appear. The August 18, 1945, Kansas City Times included a long list of metro area servicemen who would be arriving in New York after a transatlantic crossing on the ocean liner RMS Queen Mary. Their service in the European theater was complete.

Just the previous day a group of car dealers had announced that new motor vehicles could soon be arriving for sale in Kansas City. A Ford representative said the first new Fords would likely be manufactured in Detroit, since it would take some time for the Kansas City assembly plant to be converted back to civilian use. During the war it had made aircraft engine parts for Pratt and Whitney.

For the first time since 1942, there was no limit on how much gasoline motorists could put in their tank. Local filling-stations were overwhelmed as grinning customers waited in long lines to say “fill ‘er up.” A service station attendant at 39th and Main Streets in Kansas City estimated sales were up 90 percent.

The Kansas City Star of Sunday, August 19, featured a photo of a new five-room bungalow style home built in Fairway, Kansas, said to be the very first new house completed in the Kansas City area for a discharged veteran under the brand-new GI Bill of Rights. The cost of the new home was $11,000.

September 2, 1945, Official V-J Day

Gen. Douglas MacArthur signs the Japanese surrender on board the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. Harry S. Truman Library and Museum, accession number 98-2433.

After delays caused by typhoons in the area between Okinawa and Japan, the surrender ceremony on board the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay was finally scheduled to begin at 9 a.m., Sunday, September 2, Japanese time (7 p.m. Saturday, September 1, Kansas City time.)

A step-by-step account of the event was heard by radio in Kansas City at 8:30 p.m. “central war time,” September 1. The White House was linked to the USS Missouri by a global radio hook up. At a planned point in the broadcast, radio transmitters were switched from the USS Missouri to the White House, enabling President Truman to briefly address the American people (and the world) to proclaim Sunday, Sept. 2, 1945, as the official V-J Day, to acknowledge the “victory of liberty over tyranny.” Following his short speech the broadcast returned to the battleship. Gen. MacArthur concluded the ceremony in his commanding voice, intoning “These proceedings are closed.”

Truman later said that how V-J Day was to be observed would be the choice of each individual. Since there had already been a two-day federal holiday (August 15-16), plus the National Day of Prayer (August 19), V-J Day on September 2, 1945, would not be a holiday.

While a tremendous relief, Sunday, September 2 in Jackson County was quiet and anti-climactic compared with the spontaneous celebrations which had erupted on the evening of August 14th.

The signing of the instrument of surrender dominated the front page of The Kansas City Star on V-J Day. But much of the rest of the paper that day focused on the typical happenings and rhythms of a community at peace. Jackson Countians were ready to put the war behind them.

V-J Day launched an era of unprecedented American prosperity and optimism. Japan would become a U.S. ally.

Looking back 80 years later, it is worth remembering how Jackson County celebrated its most joyous time.

Source citations for this article are available by contacting JCHS at info@jchs.org

Brad Pace is a current board member and past president of the JCHS. He is a frequent writer on historical subjects.