THE KANSAS CITY MUSEUM: RESTORED AND REIMAGINED

The Kansas City Museum, located at the restored Corinthian Hall in northeast Kansas City, reopened in October.

By Brian Burnes

The Kansas City Museum, shut down for several years, reopened in October.

The refurbished museum today brands itself as “Home of the Whole Story,” a description that rings true. Since its opening in 1940, generations of Kansas City area students and visitors have found there Kansas City’s complex narrative from frontier outpost to sprawling nine-county community.

In its new incarnation the museum still tells that principal story as well as a second one – about the building itself.

Those visiting the northeast Kansas City landmark at 3218 Gladstone Blvd. will find an informed perspective of the 70-room mansion once occupied by lumber baron Robert A. Long and his family. When completed in 1910 the structure, known as Corinthian Hall, was considered Kansas City’s grandest home ever, representing the wealth then being generated by the local wholesale lumber industry.

But in more recent years the future of the Kansas City Museum had depended on the status of another large building - Union Station.

Saving Union Station

The idea of presenting the museum as a hall of science can be traced back to the 1950s and 1960s.

That’s when students from across Kansas City enjoyed its natural history and habitat dioramas as well as its planetarium, installed in the mansion’s adjacent conservatory. In the early 1960s the museum board changed the institution’s name to the Kansas City Museum of History and Science.

The restored museum includes several large wall murals. Rendered by artist Zachary Laman, the murals were funded as part of Kansas City’s One Percent for Arts program, which stipulates that one percent of public building construction costs be set aside for public art. This mural depicts SuEllen Weissman Fried, co-founder of Reaching Out from Within, a reentry and rehabilitation program for incarcerated individuals.

That emphasis endured into the early 1990s, when one study nevertheless revealed Kansas City to be one of two large cities in the country without a science museum. Some museum executives imagined new facilities separate from Corinthian Hall. Other city officials, in turn, pondered a largely empty Union Station and saw in its vast amount of square footage a separate option.

Eventually the idea of a new science museum became one of the rallying cries for a restored Union Station.

In 1996 voters in the Missouri counties of Jackson, Clay and Platte, along with those in Johnson County, Kansas, approved a bi-state sales tax to finance the restoration of Union Station. Private funds, meanwhile, were raised to establish an accompanying Science City installation.

The restored Union Station opened in 1999, with Science City a principal tenant.

In 2001 the museum board voted to merge with Union Station Assistance Corporation to become Union Station Kansas City. The Kansas City Museum Association, established in 1939, was dissolved, and just what would happen to the original museum on Gladstone Boulevard remained unclear.

It did stay open to visitors.

“But there were no changes, no visible updates,” said Denise Morrison, the museum’s director of collections and curatorial affairs.

That changed in 2008 when the city, which had acquired the museum in 1948, decided to upgrade the building’s doors and windows.

In the 1950s museum visitors often encountered natural history exhibits that included taxidermy specimen displays. (Wilborn Collection photo/Jackson County Historical Society)

In 2014 city officials opted to place the museum under the supervision of the Kansas City Board of Parks and Recreation Commissioners.

“The board under (former director) Mark McHenry really made the museum a priority,” Morrison said.

A new foundation formed to facilitate fundraising and Anna Marie Tutera became executive director.

In 2015 the museum remained open while staff and project team members developed plans to restore the mansion and reinvent the museum.

To reimagine its exhibits the museum enlisted design firm Gallagher & Associates of Washington, D.C. To lead its restoration of Corinthian Hall, the museum named International Architects Atelier of Kansas City, which initiated a master planning process for the entire 3.5 acre museum property.

The Corinthian Hall restoration represents only the initial phase of a multi-year endeavor. JE Dunn Construction of Kansas City completed its Corinthian Hall work in 2019.

Living Really Large

When originally built the mansion had been home to Robert A. Long, operator of the Long-Bell Lumber Co., his wife, Ella, and their two daughters, Sally and Loula.

Several exhibits are devoted to members of the Long family, including Loula Long Combs, a celebrated equestrienne who rode and showed horses stabled at Longview Farm, the family’s Lee’s Summit estate.

Ella died in 1928, as did Robert in 1934.

Upon their father’s death, sisters Sally and Loula took the furnishings they wanted, many of them ending up at Longview Farm, the Lee’s Summit estate where Loula resided with her husband.

The sisters then held a two-day auction to sell off remaining items. In 1939 the two sisters donated the home to the recently-formed Kansas City Museum Association, and the museum opened the following year.

But during the 24 years Long family members lived in Corinthian Hall, they had lived undeniably large.

That’s made clear by the mansion’s first floor, now restored to suggest how it appeared when the Longs were in residence.

Today visitors enter as guests likely did in 1910, encountering home’s entry hall and epic staircase. Here restorers removed layers of wax from the original marble floor, and analyzed interior paint to recreate color schemes seen more than 100 years ago. When possible, original fixtures have been retained, such as wall sconces that were removed, re-wired and reinstalled.

In the salon, on the first floor’s west side, there was a problem with the chandelier – it was missing, sold at auction in 1934.

But rather than to try to recreate the piece, Morrison said, the museum commissioned an original sculpture, rendered by Kansas City artist Linda Lighton, that includes 25 suspended and lighted porcelain flower blossoms.

Recent visitors to the museum’s restored first-floor salon admired “Luminous,” the sculpture created by Kansas City artist Linda Lighton. Featuring 25 suspended porcelain flower blossoms embedded with lights, the sculpture replaces the room’s original chandelier, sold at auction in 1934.

The home’s library, or gentleman’s retreat, remains intact, with its paneled walls and leaded glass bookcases and windows.

Some more curious interior fixtures - such as the cast bronze door handles rendered in the shape of satyrs – have been put on display.

Still other relics of the Long family’s vast resources also are visible, such as the cable works of the building’s commercial-sized elevator, considered the first installed in a private home west of the Mississippi River.

When the elevator ceased operating in the 1940s, fundraisers found money to repair it. The elevator stopped working again in the early 2000s. Today, museum officials have provided an interior view of the elevator’s cable assembly, allowing visitors to ponder seeking a contractor’s estimate for that particular Gilded Age repair.

Then there are the furnishings.

Corinthian Hall architect Henry Hoit selected New York interior decorating firm William Baumgarten & Company to acquire the mansion’s tables and chairs. Cornelius Vanderbilt, the railroad and shipping tycoon, had chosen the same firm to outfit his Rhode Island mansion known as The Breakers.

Many of Corinthian Hall’s furnishings removed by the Long sisters in 1934 since have been returned by contemporary members of the extended Long family.

Those include a tapestry and a painting, both now on display in the dining room, as well as a Dresden tea set, acquired in Germany by the family during a six-month tour of Europe in 1910.

Our City, Our Stories

One of many exhibits devoted to Kansas City history includes a detailed civil rights timeline. Among the individuals showcased is Lucile Bluford, longtime reporter and editor of The Call, a Black weekly newspaper

Today the museum’s second and third floors, once dedicated largely to bedrooms and baths, now host the museum’s changing and permanent exhibits.

There visitors can find a chronological tour of Kansas City’s history that includes familiar holdings, such as the museum’s Dyer Collection of Native American artifacts, given to the museum not long after its 1940 opening.

But the exhibits also find room for new perspectives on the impact of immigration and Kansas City’s civil rights timeline.

Also, in the museum’s “Our City, Our Stories” space, museum visitors are encouraged to examine brief, summarized stories of 21 Kansas City residents of a variety of ethnicities and backgrounds.

In still another exhibit the museum puts its own stewardship on display, detailing the care shown the more than 100,000 historical artifacts and archival materials it holds.

There are two temporary exhibit halls.

One currently showcases the Donald Piper Memorial Medical Collection of St. Joseph Hospital. The museum acquired the collection of instruments and archives in 2015.

In one exhibit the museum documents the care given its more than 100,000 historical artifacts and archival materials. The responsibility of being in the “forever business,” according to the exhibit, includes the goal of collecting and preserving objects, materials and archives “into perpetuity.”

A second hall today offers a glimpse of Kansas City’s enduring entertainment culture, vividly suggested by a large mirror ball that is a relic from the El Torreon, which once featured two ballrooms at the corner of 31st Street and Gillham Road.

The facility, which was one of the more than 100 dance halls, nightclubs and vaudeville houses that Kansas City patrons supported during the Great Depression, operated from 1927 through 1934.

The Cowtown Ballroom, a rock music venue, occupied the same space during the 1970s. In November the museum hosted a screening of “Cowtown Ballroom…Sweet Jesus,” a documentary film detailing that era.

New Generation, Revived Traditions

The building upgrade and exhibit design currently represents a $22 million investment, Morrison said.

While the response of the visitors has been positive, Morrison said, some have noticed how some attractions are no longer in place, specifically the life-sized, crawl-through igloo first installed in 1954.

“While the museum over the years never called itself a children’s museum, it had included physically interactive exhibits that allowed children to crawl into the igloo and jump up on a covered wagon,” Morrison said.

“These are things that adults of today have passionate memories of, and some of them are disappointed that their grandchildren can’t experience them.”

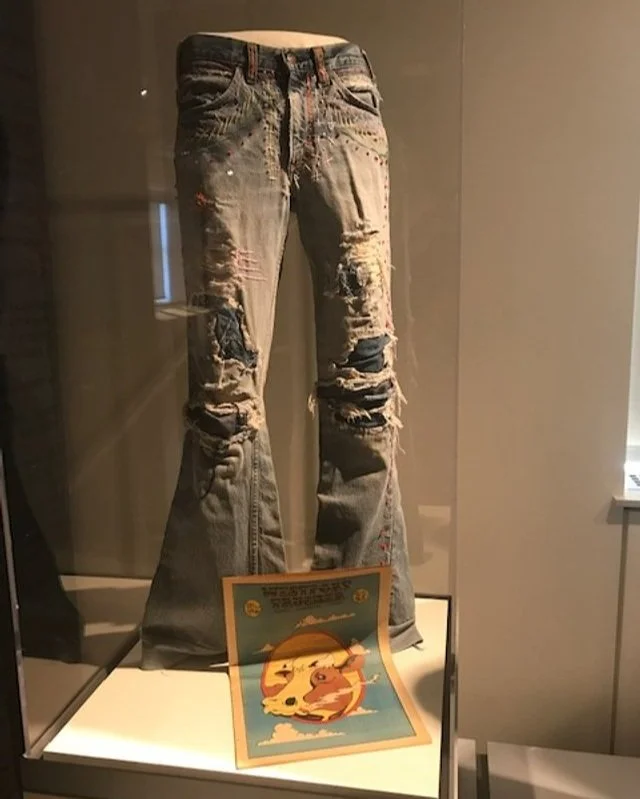

Dude - those pants. Kansas City’s counter-culture community of the 1970s is represented by this pair of embroidered bell-bottom blue jeans, once worn by siblings who attended Ruskin High School. Today they are displayed with a copy of the Westport Trucker, a Kansas City alternative newspaper published from 1968 through 1974.

Pending museum installations, Morrison added, will include several interactive exhibits that will encourage hands-on experiences.

Some museum traditions, however, have remained.

In December the museum again revived its longstanding “Fairy Princess” holiday season attraction. The tradition dates to the 1930s when Kline’s department store in downtown Kansas City introduced the princess to publicize its expanded toy department. Kline’s closed in 1970, and the museum revived the tradition in 1987.

In 2022 museum leadership hopes to welcome visitors beyond the holiday season, in part to patronize new food service options. The space once occupied by Corinthian Hall’s kitchen soon will be occupied by a new eatery, Café at 3218. The lower-level soda fountain, which opened in the 1980s, also is scheduled to reopen under the name Elixir.

“My feeling is that this is a museum for a new generation,” said Morrison.

To learn more about the restored Kansas City Museum, go to kansascitymuseum.org.

Brian Burnes is president of the Jackson County Historical Society.