Evan S. Connell

This month the University of Missouri Press has published Literary Alchemist: The Writing Life of Evan S. Connell.

The book’s author, Steve Paul, here details the publishing career of Connell, the Jackson County native whose novels Mrs. Bridge (in 1959) and Mr. Bridge (1969) examined an upper-middle class Kansas City family and served as the basis for the 1990 film ”Mr. and Mrs. Bridge,” starring Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward.

Paul, a Society member, served as a reporter and editor at The Kansas City Star for 41 years. His 2017 book, Hemingway at Eighteen: The Pivotal Years that Launched an American Legend, which describes the young Ernest Hemingway’s several months at The Star in 1917 and 1918, received the Jackson County Historical Society History Book Award.

By Steve Paul

Evan S. Connell Often Wrestled with the Character of His Hometown

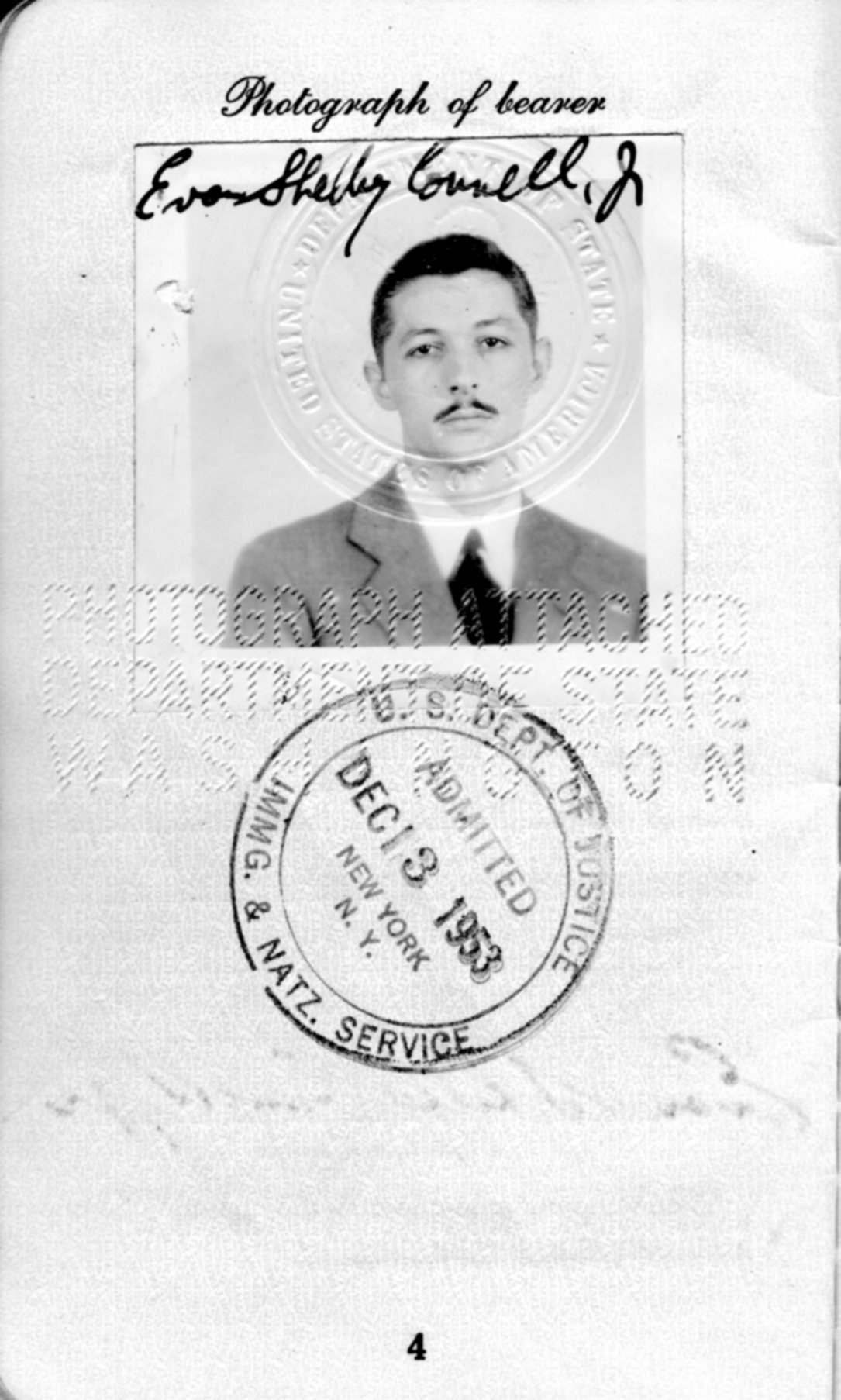

Evan S. Connell passport photo, 1953. (Courtesy of the Literary Estate of Evan Shelby Connell Jr.)

In a short story that Evan S. Connell (1924-2013) wrote early in his long literary career, a traveler has come home to a place much like Kansas City and is describing to a group of old friends the sights he saw over the previous 10 years.

The story’s unnamed narrator is a close observer of the wandering traveler J.D. and the distant sights he talks about. He notices the “wind wrinkles about his restless cerulean blue eyes, as though the light of strange beaches and exotic plazas had stamped him like a visa to prove he had been there.”

J.D.’s middle-American, businessmen friends are alternately engaged and put off by his slide-less travelogue: “He had tales of the Casbah in Tangiers and he had souvenirs from the ruins of Carthage. On his keychain was a fragment of polished stone, drilled through the center, that he had picked up from the hillside just beyond Tunis. And he spoke familiarly of the beauty of Istanbul, and of Giotto’s tower, and the Seine, and the golden doors of Ghiberti.”

When Connell wrote this story, “The Walls of Ávila,” in the 1950s, he, of course, would not have known that decades later he could find a replica of the towering “golden doors of Ghiberti” in his hometown art museum, the Nelson-Atkins. But he might well have been amused by that. He certainly would have been impressed or at least on intellectual alert that such a souvenir of the world could be transplanted to the genteel, mostly bland landscape of his youth.

Connell’s Kansas City Youth

Kansas City was the fount of Connell’s early creativity. His family life, which largely played out in the comforts of Brookside and Mission Hills, can be inferred from the pages of his best-known works of fiction, the companion novels Mrs. Bridge (1959) and Mr. Bridge (1969). Those books present an upper-crust slice of Kansas City’s social fabric as it existed in the 1930s and 1940s. The Bridge novels have—or should have—been required reading in Kansas City for decades, alternately loved for their crisp and intimate vignettes and warily regarded for their aching truths and acid views of middle-American hypocrisy.

If Connell’s own boyhood had been shaped by the Great Depression, the evidence is hard to find. His father, the eye surgeon Evan S. Connell Sr., and his mother, Elton Williamson Connell, daughter of a prominent judge, took cruises even then. In the early 1930s, Dr. Connell, who had grown up not far away in Lexington, Missouri, invested in a northeast Jackson County farmstead and soon added another one near Liberty. By the end of the 1930s, the family moved to a columned brick mansion on Drury Lane in what was not yet incorporated as Mission Hills.

The young Evan S. Connell as an Eagle Scout. (Courtesy of the Literary Estate of Evan Shelby Connell Jr.)

Connell was a product of the Border Star Elementary School and Southwest High School, each of which was a short walk away from the family’s first home, a typical Brookside colonial, at 210 W. 66th Street, with white siding and green shutters. Connell certainly benefited from a concentrated reading program at Border Star. Some of those who knew him in high school remembered him as a profoundly quiet type. And his record as a relatively average student did not project him as a creative success story.

More of Connell’s local story is reflected in another early novel, which few people have read. Called The Patriot, the book begins as the protagonist’s family gathers at Union Station to send him off to serve in the Naval Air Corps, as Connell himself did from 1943 through 1945. The Navy chapters provide alternating scenes of poignancy, self-reflection, absurd humor and some haunting, beautifully cast accounts of aviation. From there, the main character, Melvin Isaacs, continues to confound and disappoint his father. He declares that he has no interest in going to law school at the University of Missouri and instead will study art and writing at the University of Kansas, which, in fact, Connell did to complete his college education after the Second World War. (He had started out at Dartmouth.)

Connell had much difficulty writing and revising The Patriot and was never satisfied with it. Most reviewers at the time seemed to think it was a giant step backward from Mrs. Bridge, which had come out the year before. Still, The Kansas City Star found it of enough local interest to serialize a few excerpts in late 1960. Undoubtedly some of its parts are better than the whole, and I like to think that if Connell had had a better handle on it, he might have ended up with a wartime black comedy equal to Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, which came out a year later.

His Inner Midwesterner

Kansas City and versions of Lawrence, Kansas, appear sporadically elsewhere in Connell’s fiction. Late in life he confessed that though he’d long abandoned Kansas City for the West Coast and Santa Fe—San Francisco, he once said, was the best American city—he always felt like a Midwesterner. Those roots go deep.

As he writes of J.D. in “The Walls of Ávila,” “We thought he had left a good deal of value here in the midwest of America. Our town is not exotic, but it is comprehensible and it is clean.”

At another point, the narrator notices that J.D. “seemed to be struggling to remember what it was like to live in our town.”

Near the end of the story, J.D. scoffs when asked if he’d ever return home for good. On reflection, the friends recall how he’d put it: “He had explained that the difference between our town and those other places he had been was that when you go walking down a boulevard in some strange land and you see a tree burgeoning, you understand that this is beautiful, and there comes with the knowledge a moment of indescribable poignance in the realization that as this tree must die, so will you die. But when, in the home you have always known, you find a tree in bud you think only that spring has come again. Here he stopped. It did not make much sense to us, but for him it has meaning of some kind.”

Gale Zoe Garnett, a longtime friend of Connell who had a small role in the 1990 film “Mr. and Mrs. Bridge,” joined him for the movie’s Kansas City premiere that September. (Courtesy of Janet Zimmermann and the Literary Estate of Evan Shelby Connell Jr.)

As a writer, Connell left a body of work marked by a wide variety of form and substance. He was largely motivated by a search for knowledge and self. He went after anything that interested him, including subjects that had stirred his imagination in boyhood. His style, as evidenced in the passage above, was pure precision. Perhaps that came from his reading of Chekhov and other masters and mentors; perhaps it owes something to the engineering club at Southwest High School. In life, as many of his friends and acquaintances have attested, he could be ever inscrutable.

In stark, chronological terms, Kansas City and Jackson County accounted for barely a quarter of Connell’s life. He lived here less than 20 years and visited often until his parents died. In 1989, he connected with his boyhood by spending nearly 10 weeks in Kansas City during the making of the Merchant Ivory movie “Mr. and Mrs. Bridge,” an art-house conflation of the two books. He returned a year later for the movie’s premiere.

Connell had several sentimental moments during that period—chatting about Boy Scouts with the producer Ismail Merchant, and connecting, like J.D., with people and places he hadn’t seen for decades. Still, his regard for his hometown always seemed guarded, if not downright critical.

In San Francisco, he once told a Kansas City Star reporter, if he went to a party, he’d meet all kinds of people. In moneyed Mission Hills, he countered, he’d only meet people from Mission Hills.

In a letter to his sister from the early 1980s, when Connell was living in Sausalito, Calif., he describes a dinner party at the home of the writer Curt Gentry. A Hemingway acquaintance and screenwriter, Denne Petitclerc, and his wife told stories from their recent trip to Spain. “Also present were an outrageously homosexual waiter from Enrico’s cafe and a giant bartender who is also an expert professional calligrapher. So it was another quaint unmidwestern evening.” Connell had a sly and often unexpected sense of humor.

Wrestling with Kansas City’s Racial Legacy

Connell was well aware of Kansas City’s stark racial divide. That local characteristic goes back at least to the Civil War era border wars, when one Connell forebear, Gen. Joseph Shelby, rode for the Confederacy, and another owned numerous enslaved persons to tend his hemp farm next door in Lexington, Mo.

Connell wrestled with that legacy more than once in his work.

In Contact, a San Francisco literary magazine he was associated with for several years, Connell took up the troubling case of a Black couple in Kansas City, Kan., who were caught up in a school segregation case. Instead of sending their children to an inferior Black school, the family opted to teach them at home and thus ran afoul of local officials who ignored the law of the land as spelled out in Brown v. Board of Education. In an editorial, Connell’s magazine expressed concern for their plight and disappointment with local media, including The Kansas City Star, for essentially ignoring the case.

More pointedly, Connell addressed the social reverberations of race in the fictional Bridge family of the 1930s and ‘40s. Race is a constant but quiet presence in Mrs. Bridge, the first of the two novels.

In “Mr. and Mrs. Bridge,” Paul Newman portrayed Kansas City lawyer Walter Bridge while Joanne Woodward portrayed his wife India.

By the time Connell was writing Mr. Bridge, the nation had been transformed by landmark civil rights legislation and disrupted by racial protest and violence, especially following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., in April 1968. Kansas City, like other cities around the country, experienced eruptions of violent protest and police response.

Though his fictional canvas was anchored in a setting three decades earlier, Connell clearly absorbed the realities of the present as he crafted Mr. Bridge. As I write in Literary Alchemist and in an article elsewhere on race and the Bridge novels, that novel, published in 1969, clearly reflects the genteel sort of racism that defined Kansas City’s upper crust throughout the 20thhcentury and undoubtedly beyond.

In a lesser-known short story, “Nan Madol,” written more than 20 years later, Connell injects an even more overt strain of racism in a Missouri character. The narrator’s Uncle Gates, from Springfield, is visiting San Francisco, and, on a tour of the area, he makes several cringe-worthy observations about people of color. As with Walter Bridge, Connell once allowed that he was thinking of his own father, the society doctor, Evan S. Connell Sr., as he wrote this story.

Restless Traveler

The past, as well as the bucolic Midwestern landscape of Jackson County, may well be a foreign country.

Seventeen years after writing “The Walls of Ávila,” Connell returned to the template and its characters in another story that resonates in similar ways. “The Palace of the Moorish Kings” once again centers on the traveling J.D. He is “one of those uncommon men who follow dim trails around the world hunting a fulfillment they couldn’t find at home.” By this time J.D. had gone far beyond Europe, wandering “to places we had scarcely heard of—Ahmedabad, Penang, the Sulu archipelago.”

J.D. has hinted in letters that he might be ready to settle down and marry a friend from grade school, who’s now teaching in Philadelphia. Now he’s telephoning his friends to alert them of his plan. The world had become homogenized. Tourism and commercialism had spoiled the attractions. “They were putting televisions sets in bars where you used to hear flamenco,” he complained. A war in Asia “that had begun secretly, deceptively, like a disease,” was under way and had ensnared a friend’s son. Yet, nothing much else has changed among J.D.’s conservative and comfortable Kansas City friends. Zobrowski, a surgeon, tells him how irritated and envious they were that J.D. had “enjoyed yourself for a long time while the rest of us went to an office day after day, whether we liked it or not.”

Connell, forgoing Midwestern congeniality, does not tie up J.D.’s story neatly with a marriage and a visit home.

Steve Paul (Photo: Roger Gordy).