James Butler Hickok Comes to Kansas Territory

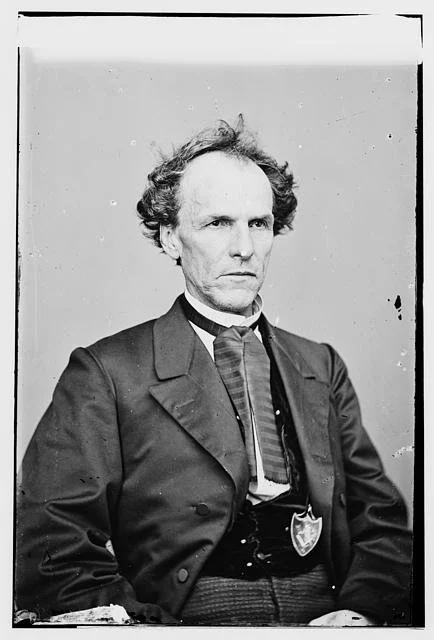

James B. Hickok, then 21 years old, in 1858 posed for this tintype in Lawrence, Kansas while serving as constable of Monticello Township in what is now Johnson County, Kansas.

(Photo courtesy of Craig Crease).

Almost everyone knows about “Wild Bill” Hickok - the legendary frontier lawman, poker player and gunfighter who died, shot and killed, in 1876 while playing cards in Deadwood, Dakota Territory, in what is today South Dakota.

Far fewer people, meanwhile, know about the incident-rich life the younger Hickok lived in what is today known as the Kansas City metro area.

In the summer of 1856 James Butler Hickok, a 19-year-old Illinois native, boarded a riverboat in St. Louis and got off in Leavenworth, Kansas Territory.

As detailed here by Craig Crease, a longtime overland trails researcher, Hickok had been drawn to the territory by descriptions of the rich farmland available there.

Today, nobody remembers Hickok as a farmer.

By 1859, as Crease writes in this month’s E-Journal, Hickok “had staked out a claim in the new Kansas Territory, fallen in love with a beautiful half-Shawnee girl, served as a bodyguard for a famous future United States senator, taken part in two battles in the Border War leading up to the Civil War, ridden for days and nights as a scout and spy in those same actions, and got his first taste of being a frontier lawman....all before his 21st birthday. He was not even known yet as Wild Bill Hickok.”

All that occurred, over just three years, to the west of the Missouri-Kansas state line.

On the Missouri side Hickok - by then widely known as “Wild Bill” - found relative quiet in Kansas City, spending much of 1872 living in or near what’s generally known today as the River Market district.

He would still grow restless, moving onto Springfield, Missouri in the fall of 1872 and then, in late 1873, joining a traveling show operated by William “Buffalo Bill” Cody and partner John Baker “Texas Jack” Omohundro for seven months before returning to Kansas City in the spring of 1874. Hickok continued his wandering before arriving in Deadwood in the summer of 1876.

He died there on August 2, 1876, at age 39.

This month’s E-Journal is adapted from Crease’s book, “The Wanderer: James Butler Hickok and the American West,” scheduled to be published on June 3.

Crease, a former Kansas City area resident, in the 1990s was among the founders of the Kansas City Area Historic Trails Association, whose members since have marked the paths of the Oregon, California and Santa Fe trails across the Kansas City metro, especially in suburban Johnson County.

Although today he lives in South Carolina, Crease remains a member of the KCAHTA executive board.

In the almost 150 years since Hickok’s death, the frontier lawman’s legend often has obscured his actual life.

In an effort to separate fact from fiction Crease, for the past 20 years, has dug deep into the historical archives, studying letters and documents written by Hickok and many others, and placing them in the context of his times.

Excerpts from those letters have been reprinted as they were written.

On June 3 copies “The Wanderer” can be purchased at caxtonpress.com and amazon.com, as well as at local booksellers. It also soon will be available at the 1859 Jail Museum, 217 N. Main St., in Independence, owned and operated by the Jackson County Historical Society.

BY CRAIG CREASE

The Hickok family emigrated from New England to Illinois in 1833. James Butler Hickok was born in Homer, IL, (now Troy Grove) on May 27, 1837, the youngest boy in a family of two girls and four boys. Young James spent his childhood and teenage years in Homer, and from all indications received a good upbringing in a loving and close family. Later life would show his family instilled in him a strong set of inner values that stood him in good stead as an adult.

James' father William was an abolitionist, with strong anti-slavery views. William was also active in the Undergound Railroad in the Illinois area. William was close friends with his neighbors the Deweys, who were abolitionists as well. A descendant of the Deweys years later recalled this event involving young James Hickok and his boyhood friend Milton Dewey:

The Dewey and Hickok families were anti-slavery people and active in the underground railroad….from time to time the boys were entrusted with the job of driving the wagon at night to the next station, the presumption being that the posse would be less likely to suspect boys than men…On one occasion when Milton Dewey and Bill [James] Hickok were driving a team made up of a Hickok horse and Dewey horse to be less easily recognized, the posse was heard following them and the boys drove off the road and into the field and spent a very nervous time rubbing the horse's noses to keep them from whinnying to the posse's horses, until the danger was passed when they proceeded to the station and made their delivery.

William Hickok died in 1852, when James was 14. In June, 1856, when James was 19, he left his comfortable Illinois home and set out with his older brother Lorenzo for Kansas Territory. The Hickok brothers were seeking the rich new farmland they had heard about, just west of the Missouri River.

In 1857 Hickok served as a bodyguard for James Lane, an ardent free state advocate who represented Kansas in the U.S. Senate after the state joined the Union in 1861.

(Library of Congress photo).

The boys traveled by foot to St. Louis, MO. Lorenzo did not care for the crowds and bustle of the big city of St. Louis and he decided to return home, leaving his younger brother to forge ahead alone. James booked passage from St. Louis to Leavenworth, KS on the steamboat Imperial. When he arrived at the riverboat landing at Leavenworth he found the landing filled with an angry crowd of pro-slavery men, intimidating the disembarking passengers. He slipped quietly through with his light baggage up the hill, away from the crowd and into Leavenworth.

IN BLEEDING KANSAS

James found himself at the flashpoint of pro-slavery and anti-slavery tension; Missouri's border with newly designated Kansas Territory.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 eliminated the so-called “Missouri Compromise” that had been in effect since 1820. The Missouri Compromise compelled parity among states; for each territory that came into statehood as a “free state,” another territory must come into statehood as a “slave” state. With that control gone after 1854, new states were free to vote which they wanted to be, “slave or free.”

The next territory to come into statehood after 1854 was Kansas. Missouri was a slave state, and had been since 1821. Soon pro-slavery elements from the south began to pour into western Missouri, hoping to affect whether Kansas would come into the Union as a slave state. Elements of free state supporters began to pour into Kansas Territory, hoping to put boots on the ground that would compel a free state when it came time to vote. In that crucible, Lawrence, KS was born.

That summer of 1856 James initially took up odd jobs around the Leavenworth area, at one point hiring himself out as a plowman. Yet that summer tensions were simmering all along the Missouri-Kansas border. That spring U.S. Senator Charles Sumner had been beaten severely with a hickory cane on the floor of the Senate by U.S. Rep. Preston Brooks of South Carolina, in retaliation for Sumner's anti-slavery speech The Crime Against Kansas.

This act lit a fire of indignation across the country. Later in the spring newly-founded Lawrence, a bastion of anti-slavery proponents, was attacked and ransacked by pro-slavery raiders led by none other than the sheriff of Douglas County, Samuel L. Jones, putting his pro-slavery views before his obligations as sheriff. The raiders ransacked the print rooms of Lawrence’s two newspapers, and then turned their cannon on the Eldridge Hotel, wreaking havoc up and down Massachusetts Street.

Three days later, in retaliation for the Lawrence raid, John Brown carried out the Pottawatomie Massacre; five pro-slavery settlers in Franklin County were killed by Brown and his men. Days later Brown and his men met pro-slavery men led by H. Clay Pate at Black Jack on the Santa Fe Trail in a pitched battle, termed by some historians as the first battle of the Civil War. Then, on August 16 , pro-slavery troops were routed at Fort Titus, north of Lawrence. At the end of August pro-slavery militia almost captured John Brown himself at the Battle of Osawatomie, a raid that resulted in the death of Brown's son, Frederick. That summer the simmering tension was erupting into violence up and down the border.

By September 1856 James was riding as a scout and spy for the free state forces. On September 1 that put him most likely with forces led by James Lane, anti-slavery firebrand and future U.S. senator, at the “battle that wasn’t,” the Battle of Bull Creek.

On August 25 the acting governor of Kansas Territory, Daniel Woodson, had declared that the territory was in open rebellion, and he asked for men to come forward to suppress the rebellion. Soon an invading force of pro-slavery militia, almost 1,600 men, was gathering near the Missouri western border, led by former Missouri senator David Atchison. Though one contingent of the men missed the rendezvous, still 1,300 men crossed the state line and headed west to Bull Creek, located in modern southwest Johnson County, Kansas. There they made their plans to find the abolitionists.

James Lane was in Nebraska when he heard of Atchison's invasion. Soon he gathered about 400 free state men, many from the Lawrence and Topeka areas. Then Lane set about moving south to find Atchison. Near dawn on September 1, Lane drew up his force in a battle line on the north side of Bull Creek.

Seeing that he was outnumbered by over three-to-one, Lane and his forces devised and executed a bold ruse. While the surprised Missourians scrambled to get into their own battle line, Lane sent one of his columns to the rear, out of sight of the pro-slavery troops, and then had them reappear outside of the opposite flank. Several times they repeated this, creating the illusion of a sizable or even superior force, more than a match for Atchison's troops on the other side of Bull Creek.

Heavy timber on the creek banks, along with the smoke of skirmishers’ gunfire in the gray of early dawn, served to cloud the vision of everyone on the battlefield. Soon Atchison and his pro-slavery troops were in a chaotic retreat, his untested and undisciplined militia convinced that a superior force was coming across Bull Creek at them. No casualties were reported on either side. Lane and his troops left the battlefield victorious, with no blood shed.

Just 13 days later James found himself in the heat of a real battle.

At Hickory Point, near present day Oskaloosa in Jefferson County, Kansas, free state forces under Colonel James A. Harvey clashed with pro-slavery forces. Though they won the battle, the free state forces suffered nine wounded and one killed. However, federal troops under the command of Phillip St. George Cooke arrived soon after the battle ended and arrested Harvey and his remaining force and took them to Lecompton, just northwest of Lawrence.

James wrote to his mother Polly back in Illinois just a few weeks after the battle, taking care to offer no details of his dangerous work for the free state forces:

….I will tell you before long what I am doing and what I have been doing. the excitement is party much over. I have seen sites here that would make the wickedest hearts sick. Believe me mother for what I say is true. I can't come home til fall it would not look well. Tell the boys all to write.

This is from your son J.B. Hickok

That same day, September 28, James wrote to his sister Lydia, complaining about not receiving more letters, and making a tongue-in-cheek remark about his commander at Hickory Point.

Dear Sister, You requested me to write to you. I returned from the border yesterday and went strate to the post office expecting to get several letters from Illinois but I was disappointed only getting one when I expected several, but I was glad to receive one from you and mother....Probably you have heard of Harvey, a Captin of a company of abolition trators. I have seen this tarable man.

Your brother J.B. Hickok.

Later that fall James wrote to his brother Horace, expressing a cynical view of his new home in Kansas Territory and revealing a little bit to his brother of the dangerous life he was leading there:

November 24, 1856

I received your letter Dated the 7 and was glad to hear from you and always be glad to get letters from home....I opend your Letter when I was Coming home this evening to see who it was from and the first thing I read you wanted to no what was going on in Cansas. I looked a head of me to whare the roads Cross. I saw about 500 soldiers a going onn and I looked Down the river and saw some nice stemers and they ware all going onn and that is the way with all the people in Cansas, they are all going on. I guess they are going on to hell. So you see I have told you what is going on in Cansas....

….iff uncle sams troops had been at hickry point fifteen minits Sooner than they ware I might have had the honor of wriding with uncle sams troops, but captin Harvey had given orders that Scouts should be sent towards Leavenworth city to see where abouts the companys of captin dun and miles Companys were camping. for you must no that they ware Camping all the while, only when provisions got scarce that they Could not help marching, and that is the way with all the proslavery Companys done.

The founders of Monticello Township established the community in 1857; Hickok served as constable there a year later. In 1988 the township was divided and annexed by several surrounding municipalities.

(Map courtesy of Johnson County Museum).

Thare is 29 of our company in custody at Lecompton yet. I have been out to see them once. I had as good a horse and as good a gun as thare was in our Company. Thare was a man Living on Crooked Crick who furnished me with a horse and rifle and revolver. What I have told you is true. I have rode night after night without getting out of my saddle. Thare is no roads, no cricks, no trails, no groves, no Crossings, no springs, no partys of any kind between Leavenworth and Lorance or Lacompt....

From your brother James to H.D. Hickok

YOUNG JAMES STAKES HIS CLAIM

In the fall of 1856 James met Robert H. Williams, an Englishman who had come to Kansas looking for land in the Leavenworth area. Williams was a few years older than 19-year-old James and, curiously, an avid pro-slavery man. Williams was with Sheriff Jones when Lawrence was raided earlier in May. James, meanwhile, was an avid free state man. Yet they became friends, and though their relationship was an anomaly, it would not be the last time that James would befriend someone with different beliefs than he.

Years later, after returning to England, Williams wrote a book about his adventures in America, titled With The Border Ruffians. He describes James Butler Hickok as “William Hitchcock,” and there is no indication that Williams realized that his friend young William Hitchcock was the legendary “Wild Bill” Hickok of later years.

In 1857 the lands of the Shawnee Indians south of the Kansas River came onto the market, as a result of the treaty that came out of the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act. Robert Williams and J.B. Hickok and several others left the Leavenworth area to seek and establish claims on the former Shawnee land in modern Johnson County, Kansas. Williams wrote about their journey:

I made up my mind to leave Leavenworth and settle in Johnson County, across the Kansas River in the Shawnee Country, intending to make my claim on Cedar Creek my headquarters. Forth I fared then, with my wagon and a pair of horses, my saddle-horse, provisions, whiskey, arms, and blankets, taking with me four of my claim-making party. These were named Shoemaker, Mike McNamara, William Hitchcock, and Wash Gobel, all who agreed to stand by me no matter what happened....I found that things were moving pretty fast in the reserve, and that joining the claim I had made on the Laramie and Kansas City road, a town had been laid out, which had been named Monticello, and that a tavern, groggery, and several shanties were in the course of erection.

James did not immediately make his own land claim upon arrival in the new area. Instead he worked breaking ground for Robert Williams. Although he did spend some time with Williams, that spring James also stayed with his friend and fellow bodyguard John Owen. That spring of 1857 found John Owen and J. B. Hickok serving as bodyguards for James Lane.

Bayless S. Campbell lived in Highland, KS in 1857, and he recalled Lane speaking there. Campbell observed two men get off their horses and lie down in the grass near the foundation of a new hotel being built where Lane was speaking. Campbell recognized the men: These two men were General Lane's bodyguard, and one of them was Hickok. The other man was John Owen. Campbell saw Hickok with Lane another time at Grasshopper Falls, Kansas (modern Valley Falls). Lane was giving a rousing anti-slavery speech on a wagon that had been pulled up for that use. An unknown pro-slavery proponent took exception to Lane's remarks, and menacingly pulled out his pistol. Hickok drew his pistol and covered the man, who quickly shoved his pistol into the holster and made his exit.

S.T. Seaton, editor of the Johnson County Democrat in the 1920s, reported what a friend, Fred McIntyre, recalled about J. B. Hickok in Johnson County in 1857:

….I went out this morning to see my friend Fred McIntyre who knew Hickok, and is perhaps the only man now living who knew him when he lived in this county, unless it is Sol Coker who now lives in Desoto and is very aged....McIntyre was a boy about 11 years old when he knew Hickok. The McIntyres lived on the section cornering the old town of Monticello on the N.W. He remembers that Hickok broke some prairie for R.H. Williams who owned the quarter adjoining the Monticello town site on the west. He used a lever plow and McIntyre used to get up and ride with him. He remembers that Hickok in those days was a good horseman and handy with a gun.

In 1857 Hickok filed a claim on land in what is now Lenexa. In 1990 the Lenexa City Council approved a recommendation to name parkland for Hickok at 85th Terrace and Clare Road, located at or near that claim.

(Photo courtesy of City of Lenexa, Kansas).

By the fall of 1857 J.B. Hickok had filed his own claim to a 160-acre quarter section about a mile southwest of Monticello, in modern-day Johnson County, and three quarters of a mile south of the California Road (Robert Williams’ “Laramie and Kansas City road “ noted above.) This California Road was teeming in 1857 with west-bound emigrants trying to reach the Oregon-California Trail near Lawrence. Border War dangers had driven emigrant traffic off of the Oregon-California Trail, located further south in Johnson County to this comparatively safer northerly route from Westport to Lawrence. It also would have been the road that James used for the short distance to Monticello and further west to Lawrence and Lecompton. On this quarter section James built a cabin, and fished out of the waters of Clear Creek, which bisected his claim. In February 1858 he went to the Land Office at Lecompton to file a declaratory statement to further the process of gaining final ownership of his claim. In April he wrote to his sister Celinda:

Today the grave of Mary Owen Harris-Hagan, referred to as “my gall” in letters sent by Hickok to his Illinois family in the late 1850s, can be found in Monticello Union Cemetery in what is now Shawnee, Kansas. The relationship ended, and Owen married a doctor named Simeon Harris; following his 1860 death, Mary remarried.

Monticello April 22nd, 1858....you ought to see me fishing on my Clame. I can ketch any kind of fish that I want to. I have fed my fish till they are all tame. The girls Comes to my Clame a fishing some times and that I don't like, but I Can't help my self, this is a free country, every on dze as he [pleases]....from your effectionate Brother James Butler Hickok.

UNLUCKY IN LOVE

That spring of 1858 brought another distraction from farming his land, the attention of a beautiful young woman named Mary Owen.

I would have finished this letter yesterday But was not at home. I was over at John Owen. I go there when I get hungry. Jest the same as I used to Come home to mothers to git some good things to eat. mary cut off a Lock of my hare yesterday and Sayed for me to Send it to my mother and Sisters. If she had not thought a great deal of you all She would not have cut it off for She thinks a grate deal of it. At least she is always Coming and Curling it, that is when I am hare.

So wrote James in August 1858 to his family in Illinois about Mary Owen. Born on April 24, 1841 to John Owen (Hickok's partner in guarding James Lane) and his Shawnee bride Patinuxa, Mary was their only child. When Mary was a toddler the family lived on the Shawnee reserve, until a flood in 1844 wiped out their little homestead near the Kansas River. After the flood John Owen found employment with the Chouteau fur trade operation on the Shawnee reserve. In 1850 Mary started school at the Shawnee Methodist Indian Mission located on the Shawnee reserve in the northeast corner of modern Johnson County, Kansas, and run by the county's namesake, Thomas Johnson. Mary lived in the dormitory at the mission during the school year. On her second year there records show there were 100 children attending, 47 of whom were girls.

By 1856 Mary was 15, and had completed her education at the mission. When she met James in the spring of 1857 she was a beautiful young woman barely 16 years of age. She caught the attention of Robert H. Williams as well. Years later he recalled:

If there was plenty of hard work, there was also plenty of good fun too, and many a good dance we had that winter. [the winter of 1857- 1858] We all of us girls as well as men, had to ride long distances to many of these, through the keen, frosty air, and the rides were almost as good fun as the dances. One of these, I particularly remember, was held at Olathy, the county seat of Johnson County, on New Years Eve. The occasion was the opening of a new hotel at this place, which was about ten miles from Monticello. I got together a party of five girls and seven or eight young fellows, all well mounted. It was a lovely starlit night, with an intense frost, and six inches of snow on the ground. All were in the wildest of spirits, and the gallop over the level trackless prairie was delightful.

At the hotel we found quite a big gathering, and as soon as the ladies had divested themselves of their wraps we were all hard at work at the cotillions and polkas. Our host had provided an excellent supper, and of course liquid refreshments were in abundance....At many of the dances I have spoken of, I often met Shawnee half-breed girls, daughters, some of them, of well-to-do people and fairly well educated, others barely “tame.” Amongst the first I remember the two Choteaus, and Mary Owens and Sally Blue Jacket. They all dressed like other Western belles, and were good dancers: but some were prone to take a little too much whiskey. Once, when dancing with Sally Blue Jacket, who was a remarkably handsome girl, she pulled a flask of whiskey out of her pocket and pressed me to join her in a drink. It would have been rude to refuse so delicate an attention, from so charming a partner, and I of course accepted the offer.

Sally Bluejacket, the daughter of Charles Bluejacket, a tribal leader of the Shawnee, went on to marry Johnson County's first county attorney, Jonathan Gore.

Mary Owen captivated James' heart, as evidenced by his letters home:

I went to see my gall yesterday, and eat ears of Corn to fill up with. You ought to be here and eat some of her buiskits. She is the only one I ever Saw that could beat mother making buiskits you no I aught to know for I can eat a Few you no. I [ate] ears of corn last Sunday. My gall washed them for me and a pack of dried corn and then was hungry.

James' family back in Illinois had misgivings about his romance with Mary Owen. They were afraid that he might marry this half-Shawnee girl. The family dispatched James' older brother Lorenzo to Kansas Territory to try and break the couple up. James tried to relieve his families anxiety with a letter to his sister Celinda:

Monticello April 22nd 1858

My dear sister....If I yoused you bad sometimes when I was angry you must forget it....you did not think I was in earnest when I spoak of marrying did you. Wy I was only joking. I could not get a wife if I was to try. Wy I am homlier than ever now days and you no that the wimmen don't love homly men....

James did not marry Mary Owen. Lorenzo may have been persuasive, or perhaps James and Mary just drifted apart, as young couples sometimes do. Whatever transpired between them, by 1859 their relationship was over. Soon Mary was being courted by a new suitor; Simeon H. Harris, a 24-year-old doctor. On October 17, 1859 he married 18-year-old Mary Owen in Monticello.

Tragedy struck the young bride; after only 14 months of marriage. Dr. Harris died of unknown causes, shortly before Mary gave birth to their only child, a boy that Mary named Simeon. Two years later Mary wed again, this time to Thomas Hagan. Yet shortly after this marriage began, Mary herself died of unknown causes on Feb. 11, 1864 at the age of 22. The author and Hickok historian Gregory Hermon described her bittersweet legacy:

In her teenage years she knew the love of a man who would become one of the most famous and respected men in the annals of the Old West. Yet, she never knew the legendary “Wild Bill” Hickok. One of the tragedies of her life was that she died before the legend began.

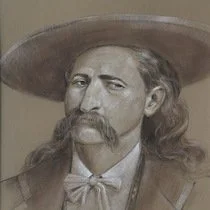

Charles Goslin, Kansas City area muralist and historian, rendered this portrait of Hickok in the 1960s. (Jackson County Historical Society).

Mary Owen is buried in the little Monticello cemetery in Johnson County, not far from the land that James claimed as his own in 1858.

THE LAWMAN

Montecello Monday 16th 1858 [August]

I will write a few minutes While dinner is cooking. I have been and served three summonses this morning. There have been 25 horses stolen here Within the last ten days by to men by the names of Scroggins and Black Bob. They have narry one been taken yet, but I think they will ketch it soon. If they are caught about here they Will be run up awful soon to the top of Some hill, I guess, where they won't steel any more horses.

James Butler Hickok is above describing a day in the job he had undertaken in the spring of 1858, as constable of Monticello and his first stint as a lawman. It was an inauspicious start in law enforcement for an unknown young man who would go on to be the most famous of the frontier peace-makers in the old West.

James was appointed constable of Monticello on March 22, 1858. He was 20 years old.

The election results that day included two names very familiar to James; Robert H. Williams as chairman of the Board of Supervisors, and John Owen as a member of the Board of Supervisors. These commissions were issued on April 21, 1858 by Kansas Territorial governor James W. Denver. Surviving court records refer to James as both J.B. Hickok and William Hickok. S.T. Seaton recalled in 1924 James' days in Monticello as a lawman:

Hickok was a constable while he lived here, and the late J.L. Morgan of Desoto told me that he and Bill [James] often rode together serving papers, and that Bill was handy with a gun.

Monticello records indicate that James was one of the arresting officers of an accused murderer, in the first murder trial to ever take place in Johnson County.

In this undated statement thought to be from early 1858, James finally admits to his family back in Illinois that the hardscrabble Kansas Territory and the rough Monticello area is very dangerous, the same area where he soon became constable:

….It was the first time in my life that I ever saw a fight and did not go out to see it, and I am glad of it now. You don't know what a Country this is for drinking and fighting, but I hope it will be different some time and I no in reason that will when the Law is put in force. There is no Common Law here now hardly at all. A man Can do what he pleases without fear of the Law or anything els. Thare has been two awfull fights in town this week, you don't know anything about sutch fighting at home as I speak of. This is no place for women or children yet, all though they all say it is so quiet here....if a man fites in Kansas and gets whipped he never says anything A bout it, if he does he will get whipt for his trouble....

ADVERSITY

As the year 1859 came around James found himself facing several difficult issues. Not only had his relationship with Mary Owen ended, but he was faced with a startling revelation about his claim; the land that he had claimed, worked and farmed was not going to be his.

The quarter section that James had claimed was located on a so-called “floater.” Even though it was on the Shawnee Indian reserve that had been opened to settlement by the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, the particular land James had chosen was actually held by the Wyandot Indian tribe as a floater. By the terms of an 1842 treaty the Wyandot tribe gained the right for certain tribal members to choose up to 640 acres on Indian land west of the Mississippi River. Of these 35 various square-mile sections, James' land was located on Wyandot Float #18. Though James had filed his claim at Lecompton on February 10, 1858, Wyandot Samuel McCullough had exercised his floater option and filed his claim on it on April 1, 1857. The Lecompton office was either not aware of this floater claim when James filed, or failed to inform James at the time that there was such a claim on the property.

Adding insult to injury, James' cabin burned down. Some speculated that the fire was set by pro-slavery men, or by someone who did not appreciate Hickok’s law enforcement actions as a constable.

Faced with these setbacks, James returned to Illinois in the spring of 1859, and went to work on a wheat farm helping to bring in the spring harvest. Curiously, it appears that he did not contact his family when he returned to Illinois, though he was working on a wheat farm just 35 miles from Homer. Perhaps he felt he had let his family down, and had no land and nothing else to show for the almost three years he had been away from home. Perhaps he wanted to save up some money from working on the wheat farm, and planned to return to Kansas Territory to begin again. Whatever the reason, the family has no record of him visiting home in 1859.

Charles Gross, who knew Hickok well later years in Abilene, Kansas, recalled:

….way back in 1859....I was sent to a farm near Tiskilwa, Ills. and put to work in the harvest field, the job being to carry water to the wheat binders. I was put to sleep with a young man named James B. Hickok, he lived there somewhere....Bill [James] was a good worker, much older than I strong and athletic. At noon and after work he pitched horse shoes, ran races, jumped, Wrestled, and was the best at the game of others there.

James returned to Kansas Territory after the spring harvest. Soon after James returned, his brother Horace moved there as well. Polly Hickok believed that Horace would be a good influence on James.

But by August 1859 James had already moved on; he was riding shotgun on the Jones and Cartwright stage between Leavenworth and Denver. Polly wrote to Horace:

Homer August 16, 1859

I was sorry to hear that James had gone to Pikes Peak. I do not know what he means by doing this as he has by not writing to us.... If you hear from him I want you to let me know for I am very uneasy about him.....I was pleased when I heard that you had gone to Kansas instead of the Peak for I thought it would be much better for you and James both if you are together but it seems you did not stay together long.

By the summer of 1859 James Butler Hickok's life had moved beyond Monticello and Johnson County.

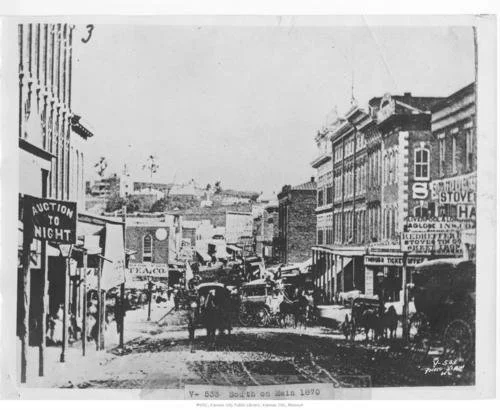

Kansas City’s Main Street In the early 1870s would have been familiar to Hickok, by then famous as “Wild Bill” after his years as a lawman in Abilene and Hays, Kansas.

(Photo courtesy Missouri Valley Special Collections).

In three short years he had staked out a claim in the new Kansas Territory, fallen in love with a beautiful half-Shawnee girl, served as a bodyguard for a famous future United States senator, taken part in two battles in the Border War leading up to the Civil War, ridden for days and nights as a scout and spy in those same actions, and got his first taste of being a frontier lawman....all before his 21st birthday. He was not even known yet as “Wild Bill” Hickok.

FINDING PEACE IN KANSAS CITY

James Butler Hickok first came to the Kansas City area in 1856, an intelligent and daring but unknown young man, seeking land for his family to homestead.

When he returned in 1872 to live in Kansas City, he came as a nationally-known living legend, having just served as the sheriff of Abilene, KS, policing the rough-and-tumble town built around entrepreneur Joseph McCoy’s experiment in transporting Texas Longhorn cattle to markets in the eastern United States.

Before that Hickok played the same role in hardscrabble end-of-the-tracks Hays City (today Hays, KS). By the time he came to Kansas City, the 35-year-old Hickok, now known all over the country as “Wild Bill” Hickok, was looking for some respite.

“The Wanderer: James Butler Hickok and the American West,” is scheduled to be available on June 3rd.

Hickok moved into the St. Nicholas Hotel, located on the southwest corner of Fourth and Main streets. The hotel stood right across the street from the Kansas City police headquarters of the 1870s. A bit further south at 520 Main St. was the Marble Hall Saloon that came to be Hickok’s favorite place to gamble. Across the street, at 529 Main St. stood the tall brick building that housed the meeting room of the International Order of Odd Fellows.

Craig Crease.