Building Chanute’s Bridge

By David W. Jackson

As a historian, I am drawn to Kansas City and Jackson County’s origin stories. And, the building and opening of the Hannibal Bridge may be Kansas City’s ultimate origin story. Officials dedicated the span - the first permanent bridge across the Missouri River - on July 3, 1869.

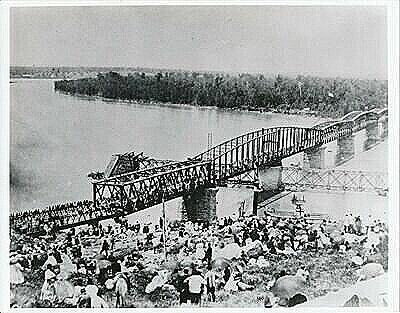

An estimated 30,000 people on July 3, 1869 attended the Kansas City dedication ceremonies of the Hannibal Bridge, the first permanent span over the Missouri River. An engraving of this photograph appeared just over a month later in “Harper’s Weekly,“ a national periodical.

Less than two months earlier, boosters at Promontory Summit in Utah Territory celebrated the driving of a final, golden, spike, joining together the Central Pacific Railroad from Sacramento and the Union Pacific Railroad from Omaha. The moment represented – at least to its champions at the time – the completion of the first transcontinental railroad in America. But, they were somewhat premature. I believe the completion of the Hannibal Bridge – connecting Kansas City and the territory to its west to Chicago and points east - to be more the transformative event. A permanent bridge spanning the Missouri River at Omaha, Nebraska, and Council Bluffs, Iowa, it should be noted, would not open until four years later in 1873.

The Hannibal Bridge, meanwhile, truly linked two vast sections of the country and – not incidentally –prompted the re-imagining of the future prospects of the frontier community at the confluence of the Missouri and Kansas rivers. I’ve long believed the significance of what first was called “The Kansas City Bridge” has been routinely undervalued. Not only did the bridge make the growth of Kansas City almost inevitable, its legacy now includes more than 150 years of events pivotal not only to Kansas City but the country. David McCullough, who spent 10 years preparing his 1992 Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Harry Truman, seemed to share this sentiment.

“I cannot think of another landscape of similar size that has had so much American history as Jackson County, Missouri,” McCullough said after completing his book. Little of that history would have happened without the Hannibal Bridge.

Wrought and cast iron

The politics involved in securing the bridge for Kansas City are familiar and have been told before, most notably in “Kansas City and the Railroads: Community Policy in the Growth of a Regional Metropolis,” first published in 1962 by historian Charles N. Glaab. That book details the nation’s emerging rail infrastructure and the intense competition among several mid-19th century Missouri River trading centers whose leaders competed for the bridge project.

The Hannibal Bridge made possible a railroad connection between Kansas City and Chicago and points east. The first steam locomotive to cross the bridge after its 1869 completion was the “Marlboro.”

By the late 1850s, area boosters had built a rail line from the northern bank of the Missouri River at Kansas City 54 miles north to Cameron, where it linked up with the Hannibal & St. Joseph railroad. That line soon would offer northern Missouri communities access to Chicago.

By then the battle was on

Officials representing Leavenworth and Atchison in Kansas and St. Joseph in Missouri competed with their Kansas City counterparts, knowing a bridge across the Missouri River could bring the nation’s bounty through their communities.

Ultimately the Kansas City boosters won congressional approval for the project. The bridge’s completion in 1869 contributed to the growth of a meatpacking district that soon became Kansas City’s dominant industry, processing the cattle being driven from Texas into southern Kansas, where rail lines had been built to ship them a short distance northeast. The city’s population of perhaps 4,000 in 1865 grew to 32,000 by 1870. Kansas City’s Union Depot, built in the West Bottoms in 1878, became one of the busiest in the country.

But how was the bridge actually built?

The two volumes I’ve recently published, Engineered Irony: Crossing Octave Chanute’s Kansas City Bridge for Trains and Teams, 1867-1917, focus on the bridge’s construction and its nearly 50-year lifespan. The first volume includes the 1870 report, ‘The Kansas City Bridge,’ submitted by engineers Octave Chanute and George Morison. It includes chapters devoted to the bridge’s foundations, masonry and superstructure. The volume also includes a new Chanute biography prepared by area expert Bill Nicks, and a separate essay focusing on the Kansas City bridge’s importance to engineering in the mid-19th century, written by area engineer and past Jackson County Historical Society Board member Brian Snyder.

The second volume includes my work over the last 10 years investigating the bridge’s construction, including revisiting in great detail the 1869 opening and dedication ceremonies.

Among the approximately 1,500 workers employed on the bridge’s construction were several divers who submerged themselves in the Missouri River current to affix one of the bridge piers to bedrock well below the water surface. This colorized engraving of a photograph taken in March, 1869 later appeared in “Leslie’s Weekly,” a national publication.

Volume two also includes a roster of employees that I compiled from original railroad records archived at the Newberry Library in Chicago. Nearly 1,500 individual laborers and contractors were involved on the project between 1867 and 1869. Most were transient workers who appear to have followed the railroads. I also re-discovered and pay tribute to a handful of workers who died building the bridge (plus, one who met his death during its deconstruction in 1917). I’m very proud of the comprehensive bibliography of just about every source I could find on the bridge, as well as a comprehensive gallery of every image of the bridge over its lifespan.

Chanute, who moved to Kansas City with his family from Chicago in 1867, designed the bridge to be built with wrought iron and cast iron. The work started with the construction of seven piers. Workers used caissons, large watertight oak enclosures that were lowered slowly into the riverbed.

There the laborers toiled, removing sand to reveal the rock below. Workers then poured concrete to form a foundation and then – on top of that – placed locally quarried limestone.

One aspect that also interested me during my research was how primary documents and other historic materials related to the bridge are scattered in different institutions across Kansas City and the Midwest. The complete story of the Hannibal Bridge – arguably the most significant event in Kansas City history –cannot be found at just one institution. I wanted this 150th commemorative edition to consolidate for the first time, heretofore long-lost data about the building of the Hannibal Bridge. I found crucial materials at several area locations, such as the Kansas City Public Library and the Kansas City Museum.

On the campus of the University of Missouri-Kansas City, I found materials both at the State Historical Society of Missouri–Kansas City Research Center as well as in the LaBudde Special Collections department in Miller Nichols Library. I found still more information at the Spencer Research Library at the University of Kansas, the Kansas Historical Society in Topeka, and even the Missouri Historical Society in St. Louis.

Bridges to the past, and future

After completing the Kansas City bridge, Chanute enjoyed a long career. He designed the Kansas City stockyards and platted the Kansas City area suburb of Lenexa. In later years, his research into elevated railroads contributed to the New York City rapid transit system. A longtime aviation enthusiast, in 1894 Chanute published “Progress in Flying Machines,” which influenced the work of flight innovators Orville and Wilbur Wright, with whom Chanute worked. Chanute died at age 78 in 1910.

This image, taken from the Missouri River’s south bank, captures the bridge under construction, with workers standing on the span and the steamboat Gipsey, which played a role in the project, passing through.

His Kansas City bridge would stand for almost 50 years, before being replaced by the Second Hannibal Bridge in 1917. That bridge still stands. Today it serves as a railroad crossing just east of the John Jordan “Buck” O’Neil Memorial Bridge, formerly known as the Broadway Bridge. That triple-arch bridge - carrying U.S. Highway 69 across the Missouri River and connecting downtown Kansas City to Charles B. Wheeler Downtown Airport and many points north - was completed in 1956.

In 2016, area leaders renamed the span for Buck O’Neil, the beloved player and manager of the Negro Leagues’ Kansas City Monarchs.

A new $220 million replacement Buck O’Neil bridge is expected to be completed by 2024.

It, like the original Hannibal Bridge, will make possible future events and careers that may continue keep Kansas City ‘on track’ with our nation’s history.

Consider that if the Hannibal Bridge had not been constructed in Kansas City, another town upriver might have become the “Heart of America.” Without that bridge, we wouldn’t have had, for instance, a garment district that rivaled that of New York City, when one of every seven ladies’ dresses and coats was “Made in Kansas City.” But with the bridge, our historic meatpacking industry arguably would become just as consequential as Chicago’s, our parks and boulevard system would be emulated across the country, and the Pendergast political machine that would dominate early 20th century also would produce Harry Truman, the country’s 33rd president.

Author David W. Jackson, former Jackson County Historical Society archivist, published the two volumes of “Engineered Irony” to observe the recent 150th anniversary of the bridge’s 1869 completion.

Kansas City without the Hannibal Bridge may never have claimed one-time or full-time Kansas City area residents who became American originals like animator Walt Disney and his famous mouse, Mickey; actors Jean Harlow, Ginger Rogers, Joan Crawford, William Powell, even Ed Asner, Don Cheadle, and Ellie Kemper; jazz musicians Jay McShann, Charlie “Bird” Parker, and William “Count “ Basie; artist Thomas Hart Benton; greeting card innovator Joyce Hall; sports entrepreneurs Ewing Kauffman and Lamar Hunt; and athletes George Brett and Leroy “Satchel” Paige.

Any one of Kansas City’s origin stories and the countless people who have come and gone . . . through our challenges and triumphs . . . are worthy of documenting as I have done in Engineered Irony.

Let’s continue to bridge those connections like Octave Chanute did 150 years ago. The train is leaving the depot. Tickets! Tickets!

The Author

David W. Jackson, former archivist for the Jackson County Historical Society, has served as archivist and director of The Orderly Pack Rat, (orderlypackrat.com), a Kansas City area research and consulting service and publishing house he founded in 1996. He has added to local history bookshelves on his own or in concert with others more than 40 titles since 2000. He continues to support the mission of Jackson County Historical Society.